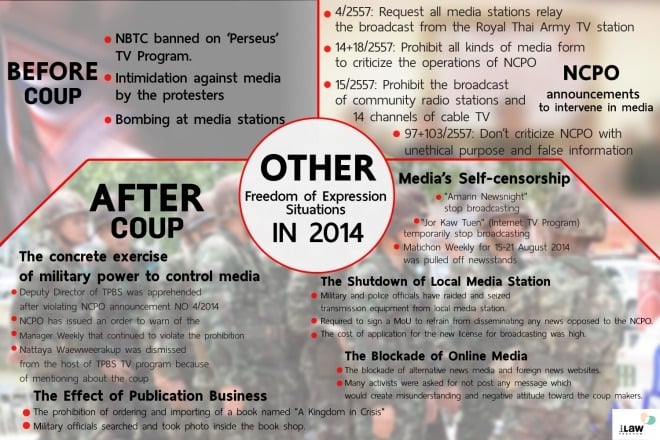

At the beginning of 2014, the heated protests of the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC), which had begun in November 2013, were ongoing. The protests continued until 20 May 2014 when the Royal Thai Army claimed that the PDRC and other political protests could lead to unrest and violence and therefore declared martial law. Two days later, they announced that they had seized power and imposed severe restrictions on the exercise of freedom by citizens and the dissemination of information by the press. By the end of the year, neither a loosening of the clampdown on press freedom nor the restriction of the freedom of the people was in sight.

In addition to summoning at least 666 individuals and prosecuting at least 134 persons for dissenting peacefully, at least 23 cases concerning lèse majesté, or Article 112, and the prosecution of at least 28 individuals for taking part in a public assembly of five or more persons or being involved in the incitement of violence have been initiated. Martial law was invoked to restrict the right to freedom of expression of the people and mass media on both large and small scales.

Pre-coup Events (1): The NBTC continues to exert its power

On 9 April 2014, the National Broadcasting and Telecommunications Commission (NBTC) set up a center to monitor radio and TV broadcasts in order to monitor the dissemination of illegal information, advertisement fraud and other content in violation of Article 112 of the Criminal Code.

On 12 April 2014, the NBTC revoked the license of “There is an answer to every question,” a TV program broadcast via H Plus satellite station hosted by Mr. Kathaphon Kaewkan. He was accused of having made a statement deemed to constitute exploitation of consumers.

Pre-coup Events (2): Intimidation of media by civic groups

The PDRC demonstrators were active in Thai politics from late 2013 until the middle of 2014 prior to the coup. The PDRC had significant support and announced a shutdown of Bangkok and demanded a new form of government. Their mobilization affected media independence.

On 16 January 2014, Mr. Tahnis Sudto, a photographer for The Nation, was allegedly physically assaulted at a demonstration site of the PDRC in Lumphini Park.

On 24 February 2014, Buddha Issara, a core member of the PDRC, led his supporters to block the entrance to VoiceTV and announced that they would stay there overnight to inform the public of the truth.

On 4 March 2014, Buddha Issara and his supporters went to the NBTC office and submitted a petition letter. They claimed that Asia Update had disseminated misinformation and misled a number of people and demanded that the NBTC revoke the channel’s license.

On 18 March 2014, core PDRC members and demonstrators went to Imperial World Department Store in Lad Phrao, which is where Asia Update was broadcast and was also the site of press conferences of the United Front for Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD). They demanded that the owner of the building refuse to allow the UDD to rent the venue.

On 7 May 2014, a German photojournalist, Nick Nostitz, was intimidated by three men in front of the office of the Constitutional Court while he was covering the decision of the Court regarding the transfer of Mr. Thawin Pleansri. Nick confirmed that the assailants were PDRC guards and wore the emblem of the PDRC.

In addition, unknown groups used violence to intimidate media workers engaged in reporting. There were at least two incidents of intimidation prior to the coup.

On 7 February 2014, a grenade was thrown into a community radio station, the Red Guard station of Ko Tee located in Pathumthani. One person was injured. Then, on 26 March 2014, unknown assailants fired at a red shirt community radio station in Mae Sot in Tak province, also belonging to Ko Tee. Twenty (20) Kalashnikov bullet shells were found and one person sustained an injury to his right arm.

On 24 April 2014, unknown assailants fired M79 grenades into the headquarters of the Daily News.

The atmosphere of fear and concomitant expectations from various political forces for media impartiality caused many media outlets to engage in self-censorship and attempt to paint their stations as neutral. For example, Pornthip Muangyai, a reporter for Mono 29, decided to stick tape over her mouth while being pictured with a row of military men on 22 May 2014. The following day, the Mono Group declared publicly that her action was only her own opinion and had nothing to do with the company. They maintained that they were impartial and were not affiliated with any political parties. On 23 May 2014, Pornthip Muangyai was fired from her position.

Imposition of restrictions on freedom of the press and the people by the Army after the coup

After the Army imposed the 1914 Martial Law Act on 20 May 2014, a series of announcements and orders were issued to control the media. The authorities claimed that they issued these measures in order to “ensure that people from all sides receive information that is correct and will contribute to public order.” These measures included the following:

Peace and Order Maintenance Command (POMC) Order No. 3/2014 prohibited reporting, dissemination and distribution of publications which may affect the maintenance of public order maintenance.

POMC Order No. 9/2014 prohibited provocation of conflict or opposition to the operations of the POMC. In sum, press media outlets and broadcast media were not allowed to invite persons, aside from incumbent officials, to give interviews or to express opinions as they may have led to the expansion of conflict and violence. In addition, provincial governors and police were authorized to suppress any demonstrations or activities which may have been hostile to the operation of the POMC.

After the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) staged a coup on 22 May 2014, further announcements were issued to impede the exercise of the right of the media to disseminate news and information and the general right to freedom of expression. This included NCPO Announcement No. 4/2014 which requested all radio stations, TV stations, community radio stations, satellite TV stations, and cable TV stations to refrain from broadcasting their usual programming and to only relay the broadcast of the Royal Thai Army TV station in order to ensure the distribution of correct information.

NCPO Announcement No. 14/2014 is similar to POMC Order No. 9/2014 as it prohibited all kinds from media from interviewing any individuals apart from government officials and empowered the governors and police to suppress any demonstrations or activities which may be hostile to the operations of the NCPO.

NCPO Announcement No. 15/2014 prohibited the broadcast of 14 satellite, cable, and digital television channels and prohibited the broadcast of community radio stations without official licenses.

NCPO Announcement No. 18/2014 provides for the prohibition of news pertaining to seven criteria including news that is defamatory to the monarchy, incites violence and harmful to the national security, criticizes the operation of the NCPO and related persons, etc. The Announcement did not specify the punishment for its violation.

NCPO Announcement No. 97/2014 combines Announcement Nos. 14 and 18 to prohibit individuals and all kinds of media from interviewing academics and former civil servants. The Announcement notes that doing so may lead to further violence and prohibits all kinds of media from disseminating news pertaining to the seven criteria similar to those mentioned in Announcement No. 18. Punishment for violation includes revocation of operational licenses and prosecution depending on the types of offences related to the program content.

NCPO Announcement No. 103/2014 is an amendment of Announcement No. 97 after a significant outcry from media operators and a request for some leeway for media to criticize. The Announcement noted that no criticism shall be made with an unethical purpose or with false information. Any media that violates the Announcement can be referred to the relevant professional media organizations for ethical inquiry.

In addition, the NCPO has issued two Announcements to suppress online media. This includes Announcement No. 12/2014 to seek cooperation from operators and persons related to online media to terminate any services used to send messages inciting violence. In addition,Announcement No. 17/2014 requests Internet Service Providers to monitor, investigate and suppress the dissemination of news and information purported to distort information and incite violence in order to cause unrest in the Kingdom or to compromise national security.

Post-coup Events (1): The concrete use of military power to control media

On 22 May 2014, the NCPO seized the ruling power of the country and issued Announcement No. 4/2014 asking all TV stations to terminate the broadcast of their normal programs in order to ensure dissemination of correct information. The same evening, TPBS decided to broadcast its normal programs via YouTube. As a result, the station was raided by military officials and Mr. Wanchai Tantiwittayapitak, Deputy Director of TPBS, was apprehended and held in custody at a military camp.

On 25 May 2014, the NCPO invited the executives of 18 newspapers for a “consultation” at the Military Club on Vibhavadi Rd.

On 13 June 2014, Chamlong Singtongam, Director of the National Broadcasting Services of Thailand (NBT), issued an order to Charoensri Hongprasong, Director of News and Program Production for Channel 11, to stop all operations as the channel disseminated news that violated NCPO Announcement Nos.14 and 18 regarding the prohibition of incitement of violence or the creation of an environment hostile to the operations of the NCPO. The order was later rescinded.

On 26 July 2014, the NCPO issued Order No. 108/2014 to warn the print media about ongoing violations of various prohibitions. The warning was issued after Manager Weekly, No. 251 (26 July – 1 August 2014), published false information that discredited the NCPO and was therefore considered a breach of Announcement Nos. 97/2014 and 103/2014. Subsequently, the next issue of Manager Weekly, No. 252, was published with a completely black cover and the magazine ceased publication for one month.

On 14 November 2014, a group of military officials met with the executives of TPBS and asked them to cease broadcasting the program “People’s Voices Which Need to be Heard Before the Reform.” The military was dissatisfied with the host of the program, Nattaya Waewweerakup, and how she alluded to the coup and framed her questions. TPBS conceded to the military’s demands and dismissed Nattaya as the host of the program.

On 15 November 2014, during a meeting chaired by the Army Commander-in-Chief at the Suranaree Military Camp of the 2nd Army Region in Nakhon Ratchasima, an incident occurred in which a military official of the Chief of Staff of the 2nd Army Region abruptly tugged on the video bag of a reporter for Modern Nine TV and pulled her out of the meeting room without any explanation. The next day, the Civil Affairs Division of the 2nd Army Region issued a statement to explain that the incident did not involve violence and the reporter was not pulled forcefully outside the meeting room. All that happened was that the straps of her camera bag were touched and she was asked to leave the room. In addition, the military also asked media outlets to disseminate correct and appropriate information and to refrain from discrediting the Army.

On 10 December 2014, Pacharapapon Pumpraphan, a news reporter from 3SD Channel, tweeted from his personal Twitter account (@Pacharapapon) about an incident in which he was reporting live at the Democracy Monument about the meaning and symbols contained in the monument. The military officials stationed at the Democracy Monument shouted at he and other reporters that they must cease taking pictures and broadcasting and that prior permission was needed for such a broadcast.

Post-coup Events (2): The political climate and media self-censorship

In addition to the direct exercise of power to stifle media freedom after the coup, the state has created a climate of fear to systematically intimidate the media through various means including the issuance of rules and regulations and the use of physical force to block, arrest and punish defiant media. As a result, a number of media workers have resorted to self-censorship to preclude being harshly punished by the military. This includes the following known cases:

Fa Diew Kan publishing house issued an open letter to subscribers on 3 June 2014 and announced the postponement of the publication of a new issue. The open letter stated that within the context of intense intimidation and monitoring of the media following the coup, Fa Diew Kan had received special scrutiny and this had engendered fear among all sectors of production of the journal. For reasons of the safety of all involved, they postponed publication for the time being.

On 10 June 2014, Pinyo Trisuriyatamma decided to resign from “Amarin Newsnight” after only one week of broadcasting. He stated that the coup had led to the transformation of the environment both inside and outside the TV station. He stated that he stood by his position and professional principles. The Amarin executives claimed his termination of service was due to a difference of opinion with the station and maintained that the parting was amicable.

Spokedark.tv, which produces the internet news program, “Shallow News in Depth – Jor Khao Tuen,” which offers a satirical view of social and political issues, decided to suspend its program following the coup. In order to fulfill their remaining contracts with their clients, the program was changed to a discussion of foreign news. The program was fully restored to its usual form in October 2014.

On 15 August 2014, Matichon Weekly No. 1774 (15-21 August 2014) was pulled off newsstandsas there was a proofreading mistake that caused a typo in a poem by “Rarin Pramook” which could have been subject to misinterpretation and therefore deemed to be in violation of the law.

On 23 November 2014, the Bangkok Post website published the first public interview after the coup with former PM Yingluck Shinawatra. The following day, however, the piece was deleted from the website and Wassana Nanuam, the interviewer, explained in a Facebook post that it was not really an ‘interview’ with Yingluck. It was simply a chat during which some trivia about life were discussed. Wassana acknowledged that she realized the former PM was not in a position to give an interview on political issues.

In addition to what has been reported publicly, military officials also allegedly dispatched forces to take control of major media outlets on the day of the coup. For several months after, a number of forces continued to be stationed at these media outlets. Officials monitored the press in editorial rooms and notified the executives and reporters when they found anything that would hurt the image of the NCPO.

Reportedly, a number of executives and reporters from news networks have been regularly summoned for meetings with high-ranking military officials. Meanwhile, the NBTC has called several meetings with radio and TV broadcasters and warned them not to disseminate any information hostile to the NCPO. Even though direct intimidation of media has been relatively infrequent, the overarching climate of fear and sensitivity has made it difficult for the media to maneuver and has eventually led to the significant compromise of public access to information.

Post-coup Events (3): Small and local media outlets shut down due to Announcement No. 15/2014

After the coup, stringent control was imposed on local media outlets. NCPO Announcement No. 15/2014 purported to terminate the broadcast by unlicensed community radio stations. The laws used to clampdown on local media can be described as follows:

It has been reported that military and police officials in all regions have raided, photographed, and seized transmission equipment from community radio stations, local cable networks and local press offices. In certain areas, people involved with these local media outlets have been asked to produce their ID cards, which were then photocopied, and to submit to DNA testing, even though the media outlets were not involved in political movements and only disseminated information about the environment and religion. Such intimidation has taken place since the evening of 22 May and has not ceased. Some media outlets have been subject to regular monitoring by the military in order to ensure that their broadcasting was brought to a complete halt. This has included the following, by region:

The North: In Chiang Mai, the Rak Chiang Mai 51 community radio station (FM 92.5 MHz), which is owned by Mr. Petchwat Wattanapongsirikul, a core member of the Red Shirt Rak Chiang Mai 51 group, was raided and closed by military officials following the coup. In Lampang, the military took control of the Democracy Lovers community radio station and the Local People’s Voice community radio station broadcast (FM 96.25 MHz). The station also hosted the office of Local News. In addition, MAP radio, a radio station for ethnic minority groups based in Chiang Mai and Mae Sot was raided by the military and forced to terminate its service which affected the right to know of ethnic minority groups.

The Northeast: People’s Voice Radio (FM 100.00 and 100.75 MHz) located in Udon Thani and owned by Mr. Anond Saennan, founder of the Red Shirt Village for Democracy in Thailand, was raided by military officials and all transmission equipment was seized. Similarly, Udon Lovers Radio (FM 97.5 MHz) was raided and shut down by the military on the evening of the coup. In Ubon Ratchathani, “DJ Toy,” a core member of the Chak Thong Rob Red Shirt group, said that after the coup, military officials came by and asked him to report himself. He was then held in custody for six nights. After being released, the military continued to call on him at his office regularly and photographed him each time.

The Central Plains: Bang Yai community radio station in Nonthaburi (99.75 MHz) decided to cease its operations on the day of the coup. The military continued to use authority deriving from NCPO Announcements to raid another radio station in Petchabun. The military raided the Idea Radio community radio station (FM 104.25 MHz) and seized their equipment. In Chachoengsao, the Khon Plaeng Yao community radio station was shut down but then allowed to resume its operations for a period. But then military officials from another unit raided the station again and claimed that they did not have permission to resume their operations.

The South: In Pattani, five plainclothes policemen raided the rented homes of a human rights activist and a radio reporter for Media Salatan without producing search warrants and claiming authority derived from martial law. The individuals were asked to produce their ID cards, which were then photocopied, and to provide their family information for the officials’ report. In Prachuap Khiri Khan, military officials visited the Bor Nok community radio station and they wanted to ensure that the station had ceased broadcasting and asked for information about the station’s operations.

In addition, state officials also asked local media to attend meetings to seek their cooperation in refraining from broadcasting any news hostile to the operations of the NCPO and news that might incite or provoke opposition among radical students including in Phayao province and inPhitsanulok province.

After NCPO Announcement No. 15/2014 was issued, all community radio stations and local cable networks which used to be allowed by the NBTC to broadcast, had to shut down immediately. Any media outlets which wanted to resume broadcasting had to seek a new license and were required to sign an MoU to refrain from disseminating any news opposed to the NCPO. A number of them received licenses and resumed their operations, although many more have not received permission to resume their operations. Several broadcast media decided against applying for a new license since they did not want to operate within the post-coup climate. Also, several community radio stations could not afford the expenses incurred in making an application for a new license, which amounted to around 50,000 baht per station. As a result, the number of local media outlets has drastically declined since the coup.

Of the more than 7,000 small community radio stations broadcasting prior to the issuance of NCPO Announcement No. 15/2014, 5,300 decided to apply for new licenses and around 3,300 stations have now been allowed to resume their operations.

Post-coup Events (4): The disappearance of vibrant online news

After mainstream media and community media became subject to strict control, online media were the last resort to maintain the circulation of information among the public. Nevertheless, the NCPO invoked martial law to block access to a number of websites, particularly political websites such as dangdd.com, uddtoday.net, uddred.blogspot.com, thaipoliticalprisoners.wordpress.com, etc. Alternative news media, including Prachatai, Prachatham News, and the Midnight University were also blocked. Worthy of note, websites of foreign news outlets, including dailymail.co.uk, standard.co.uk and some Reuters pages were also blocked.

On 28 November 2014, the Thailand section of the Human Rights Watch website was blocked. Even sports websites such as www.livescore.com and www.atpworldtour.com were subject to being blocked, presumably because they featured information useful for online gambling. Online movie websites including www.freemovie-hd.com and www2.siam-movie.com were also made inaccessible, presumably because they contained The Hunger Games, a film which inspired activists to flash three fingers as a symbol against the NCPO.

A full-length report of the online media blockade after the coup can be found here >>>https://www.ilaw.or.th/articles/8832

The climate of social media has changed. Several Facebook pages dedicated to the promotion of democracy had to shut themselves down, including the fanpages of the Assembly for the Defense of Democracy (AFDD), the Campaign Committee for the Amendment of Article 112, etc. Cyber activists decided to deactivate their accounts or tone down their content including Somsak Jeamteerasakul, Sombat Boonngamanong, etc. The result has been to make social media much less vibrant.

On 28 May 2014, internet users in Thailand were unable to access Facebook for about one hour. The Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology (MICT) told the press that the junta instructed them to temporarily shut down access to Facebook in order to preempt conflicts. The NCPO spokesperson denied this account and the Permanent Secretary of the MICT was later removed from his office.

Since the exercise of draconian power to block Facebook had too great an effect on the lives of people uninvolved in politics, the NCPO switched tactics and requested cooperation from involved individuals directly instead.

On 4 July 2014, Thanapol Eawsakul, editor of Fa Diew Kan, posted a Facebook message noting that the NCPO called him to ask for cooperation in not making any posts which might create misunderstanding or negative attitudes toward the junta. Therefore, he announced via his Facebook page that he would refrain from posting any message that might negatively affect the junta. Subsequently, on 19 October 2014, the military officials called to inform him of their displeasure and request that he remove a post in which he gave an account of “meeting and discussing with the writer Prajak Kongkirati, ” on the Fa Diew Kan Facebook page. In that post, he mentioned the attempt by the military to control the publishing house.

On 17 November 2014, the Facebook page for “Come together to permanently close the gates of Pak Mun Dam” declared that it would cease all activities. They gave the reason that military officials in Ubon Ratchathani requested their cooperation and requested that they cease mobilizing via Facebook as some powerful people were dissatisfied with opinions expressed via their page. If they failed to stop organizing, the military would use their authority under martial law to make them do so. Subsequently, on 18 November 2014, military officials called and asked Kridsakorn Silalak, the coordinator of P-Move on Pak Mun Dam issues to deactivate his personal Facebook account as he had expressed inappropriate opinions.

In addition to requesting cooperation to deactivate Facebook accounts and to remove inappropriate political posts, the NCPO also asked people to post messages generated by government officials on their personal Facebook pages. For example, Witoowat Thongbu, a member of the Network of Northeast People’s Sector Organizations and one of the signatories to a statement declaring an intention to not participate in the reform efforts of the dictatorial regime revealed that after turning himself in and talking with the military officials, he was told to stop all his campaigns against the regime and the NCPO. If he did not do so, he would face legal action. In addition, he was asked to post messages as instructed by the officials on his Facebook page. In total, he was forced to declare that he would not engage in any protests in the street or online and to agree to cooperate with efforts to develop the nation. He also pledged his support for the reform of the government and to follow the path set by the government.

Post-coup Events (5): The book industry has become a threat to national security

Following the imposition of martial law, news spread via social media that Kinokuniya bookstore had removed six books about Thai politics from their shelves. These books included Democracy & National Identity in Thailand, Legitimacy Crisis in Thailand, Bangkok May 2010 4, The Simple Truth, Making Democracy and Free Thai: The New History.

After the coup, the military raided “Book Re:public,” a bookshop in Chiang Mai and a venue for pro-democracy activities. According to the bookshop’s owner, fully armed and uniformed military officials came in and took photographs inside the shop including all books available. Staff were told not to put up any posters bearing pictures of politicians or core Red Shirt members. State officials stopped by at the bookshop three or four times a week. In addition, “Philadelphia,” a bookshop in Ubon Ratchathani, was put under close surveillance by the military given its political stance and previous activities.

On 2 July 2014, the Phan Waen Fa Award Committee decided to cancel their 13th awards ceremony which usually takes place at the Parliament. They claimed that the Committee decided to cancel the contest in light of the political situation. The award has been annually given to authors of political literature and is organized by the Writers’ Association of Thailand and the Parliament to promote parliamentary democracy with the Kind as the Head of State. It aspires to encourage people to exercise their right to freedom of expression and to support political literature underlined by democratic values.

The Book Fair held in October 2014 was the first to be organized after the coup and it was met with opposition from the military. According to the editor of Fa Diew Kan publishing house, military officials came to inspect its booth beginning the night before the opening day. They claimed that they needed to so because the publishing house was going to sell publications deemed offensive to the monarchy. In addition, the military called the Publishers and Booksellers Association of Thailand asking for permission to make video recordings and monitor the Book Fair, including a public discussion with writers organized by Fa Diew Kan publishing house, but the Association denied the request from the military and asserted its right to sell books.

On 12 November 2014, the Commander of Royal Thai Police invoked the 2007 Printing Act and prohibited the entry or importation of A Kingdom in Crisis by Andrew MacGregor Marshall for distribution in the country on the basis that it defames, insults, or threatens the King, the Queen, the Heir-apparent, or the Regent and compromises national security.

Post-coup Events (6): The exercise of robust, draconian power leads to many kinds of violations

Government officials are obliged to implement policies to restrict the right to freedom of expression in order to preserve the NCPO’s image of their regime as a return to happiness. As a result, the rights and freedom of the people have been violated in many different ways, including via the authority granted by martial law and via means in which it is unclear if the authority has a legal basis or not. This has included the following:

Local authorities and police have been asked to cooperate by monitoring and removing any banners which show opposition to the coup, the government’s operations and the NCPO in order to prevent conflict from arising. For example, banners criticizing the NCPO were removed in Chiang Mai and Ubon Ratchathani and one suspect was arrested in Yala.

Demonstrators are asked to produce their ID cards and they are then photocopied and retained as evidence by the officials. Awards are offered to anyone taking photos of anti-NCPO demonstrators, i.e., one could obtain 500 baht if his or her photo led to the arrest of demonstrators, such as those who gathered in front of the US Embassy

During the activity to commemorate the transformation of the country from an absolute monarchy into a democracy, all participants were required to register their names with the officials before entering the ceremonial ground and no balloons were allowed to float as the officials claimed that the balloons might stray into the area of the nearby Royal Palace [http://www.prachatai.org/journal/2014/06/54203] .

Similarly, during a merit making ceremony to commemorate the demonstrators who were killed during the protests led by the United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship (UDD), a dozen plainclothes police officials came to monitor the event and take photographs of all participants and make copies of their ID cards.

Another memorable event was one in which military officials used the authority granted to them under martial law to seize the utensils of a vendor selling fried squid on Thippanet Rd. in the city of Chiang Mai simply because he was wearing a red T-shirt bearing the face of Mr. Jatuporn Promphan, a core Red Shirt member. Five military officials asked him to remove the shirt without giving him a replacement and simply took it away. In a similar vein, military officials raided and seized merchandise from “@ PAI,” a booth selling strawberries and strawberry products since the booth was owned by a Red Shirt activist. The officials claimed the cartoon logo of the booth was similar to the face of Lt. Col. Thaksin Shinawatra. In addition, the restaurant Sudsanaen was raided by fully armed military officials who claimed that they received a report that a birthday party was being held for “Mom Taona,” a Facebooker who is known to support the Red Shirts. But there was no such party taking place at that time.