In early 2014, the situation of cases concerning Article 112 of the Criminal Code, or lèse majesté cases, was relatively less tense in comparison to the post-coup period. A number of verdicts made prior to the coup were in favor of the accused. The rights of the accused and society were given an importance greater than the infliction of severe sanctions. Leniency was shown, particularly to defendants with health problems.

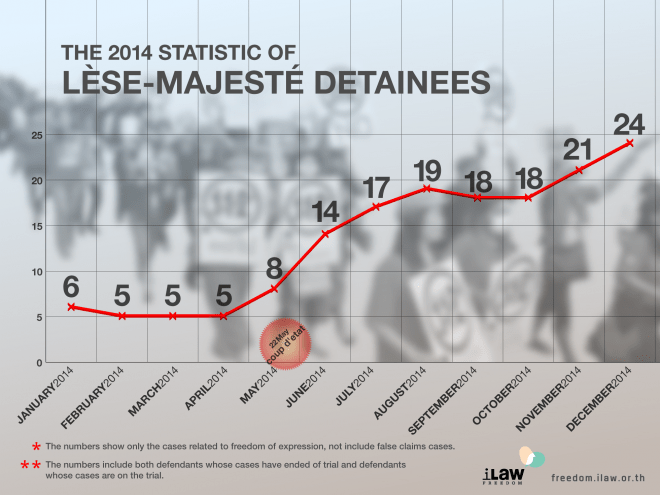

But after the 22 May 2014 coup, the number of lèse majesté cases rose sharply. An announcement was issued by the junta to empower the military court to process civilians. Secret trials and harsh punishment have been used. While the trials conducted by civilian courts helped to ease social tensions, this easing up has ceased in the post-coup political climate.

Verdicts in line with good practice created a less tense climate prior to the coup

On 17 February 2014, the Supreme Court upheld the verdict of the Court of the First Instance to sentence Bundit, who made a remark allegedly insulting to the King at a seminar held by the Election Commission of Thailand in 2003, to four years imprisonment. The sentence was suspended for two years as the accused suffered from schizophrenia and was advanced in age. The ruling by the Court of First Instance was made in March 2006; this decision had been overturned by the Appeal Court which sentenced Bundit to two years and eight months of imprisonment with no suspension in December 2007.

On 26 March 2014, the Appeal Court dismissed the case against Surapak, who was accused of creating a Facebook page featuring information insulting to the King. In an affirmation of the Court of First Instance’s verdict, the Appeal Court reasoned that the evidence presented by the prosecution failed to carry enough weight to prove the guiltiness of the accused.

On 17 April 2014, the South Bangkok Court dismissed the case against the seller of “Kong Chak Pi Sat” (Thai translation of The Devil’s Discus), a book banned in Thailand. The Court noted that even though the accused sold a book with content deemed insulting to the King, the prosecution failed to prove that the accused would have known about the content of the book and therefore there was not sufficient evidence to prove that the accused intended to commit the offence.

On 8 May 2014, the Appeal Court upheld the verdict of the Court of First Instance to imprisonEkachai for five years for selling a VCD that contained an ABC documentary and Wikileaks material. The sentence was reduced to three years and four months given that the evidence given by the accused was useful for the trial.

On 21 May 2014, the day before the coup, the Criminal Court ruled in a case against Thitinand who was accused of defacing a portrait of the King. She was found guilty and sentenced to two years in jail. The sentence was reduced to one year as she pled guilty to the charge. Further, given that the accused had no prior criminal offences and was suffering from mental illness, the jail term was suspended for three years.

Apart from the verdict made by the Appeal Court in the case against Ekachai, the other four verdicts helped to ease the tensions caused by the use of the draconian law. The accused persons who suffered from health problems or may have committed the alleged crimes as a result of health problems were sentenced to suspended terms in order to give them time to seek treatment.

In these cases, the Courts seemed to uphold the principle provided for in Article 227(2) of the Criminal Procedure Code that, “Where any reasonable doubt exists as to whether or not the accused has committed the offence, the benefit of the doubt shall be given to him.”

In addition, in the verdicts in the cases against Surapak and Thitinand, the Court did not just consider the case qua case, but also the overall political and social context as well. In the case against Thitinand, the Court viewed the suspension of her sentence as a decision that benefited the entire society, not only the accused. In the verdict by the Appeal Court in the case against Surapak, the Court ruled that returning a conviction in a sensitive case, such as a lèse majesté case without solid evidence, would simply cause further divisions in society.

It is possible that the Courts have realized that lèse majesté cases are public cases and any verdict will have unavoidable impacts on the political climate and therefore the Courts must adjust themselves. Social pressure and critiques of the functioning of the Courts and the problems of the Article 112 of the Criminal Code likely influenced the ways in which verdicts were written during early 2014 prior to the coup.

An increase in lèse majesté cases after the coup

One of the first priorities declared by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO), the coup makers, was to protect the monarchy. It was mentioned in NCPO Announcement No. 1 that, “(We) pledge to hold in high esteem and protect the monarchy.”

After the coup, attempts have been made to quickly arrest and prosecute individuals accused of committing offences against the King and the number of cases has sharply risen.

On 22 May 2014, the prosecutors indicted “Thongchai”, a resident from Chiang Mai, who was accused of tossing a flag bearing the emblem of the King into the river during a 2010 provincial Red Shirt demonstration, in the Chiang Mai Provincial Court. He turned himself during December 2010 and was granted bail while the investigation took place. The case against him is temporarily on hold due to his necessity to seek treatment for mental illness.

On 23 May 2014, Apichat was arrested during a demonstration against the coup. While he was held in custody, his mobile phone was accessed and a lèse majesté charge was later pressed against him in relation to a Facebook post he made. After being held in custody by the police for 25 days, he was released as the Court refused to extend his detention.

On 25 May 2014, the NCPO issued Announcement No. 37/2014 to empower the military court to try cases related to security as well as violations of NCPO announcements and orders and violations of Article 112. Basically, after the announcement came into force, any civilian found to have committed a lèse majesté offence is to be tried in the Military Court. While martial law is in force, the Military Court will function as a single-tiered court with no chance to appeal the verdict.

On the same day, “Somsak Pakdidej”, editor of Thai E-News, was arrested on a lèse majesté charge for publishing an article penned by Gile Ungphakorn in 2011. “Somsak” was initially held in custody at the Criminal Court but was later transferred and indicted at the Military Court. During the first hearing of the case on 24 November 2014, “Somsak” pleaded guilty to the charge and was instantly sentenced to nine years, which was then reduced to four years and six months.

On 2 June 2014, police officials arrested Yutthasak, a taxi driver whose conversation with a passenger in his car was recorded and used as incriminating evidence in a case filed against him in January 2014. Initially, he was held in custody and denied bail. On 8 August 2014, he was brought to the Court without his lawyer. After pleading guilty to the charge, he was sentenced to five years, which was then reduced to two years and six months.

On 18 June 2014, police officials arrested Akaradej, a student at Mahanakorn University of Technology after he was reported to the police for posting a Facebook message deemed to be an insult to the King in March 2014. On 4 November 2014, the Court sentenced him to five years, which was then reduced to two years and six months given that he pled guilty to the charge. In this case, the Court intervened and proposed a reconciliatory hearing during which both the accused and the prosecution agreed to make a deal and Akaradej decided to plead guilty.

On 1 July 2014, Sombat Boonngam-Anong, aka “Bor Kor Lai Jud” (Polka Dot Editor), an activist of the Red Sunday Group, was brought to the Roi-et city police station to hear a lèse majesté charge reported against him in January 2014. He was granted bail while the investigation proceeds.

On 2 July 2014, military and police officials jointly arrested “Thanet” from his residence in Petchabun. He was accused of sending an email message to a third party deemed insulting to the King in 2010. “Thanet” was suffering from illness and according to a diagnosis made by the Galya Rajanagarindra Institute (GRI), he was in a paranoid state. But he was denied bail.

On 8 July 2014, police officials arrested Samak after he had reportedly defaced a portrait of the King placed at the entrance to a village in Thoeng District of Chiang Rai Province. While being held in custody in the Chiang Rai Provincial Prison, he was indicted in the Chiang Rai Military Court. The case against him was the first in which the alleged offence was committed after the coup. He confessed to the charge and claimed that he was not aware of committing the offence since he suffered from mental illness as certified by a medical doctor. The first hearing in this case took place on 11 January 2015.

On 9 July 2014, military and police officials arrested Thanat, aka “Tom Dundee”, a pop singer and a core member of the Red Shirts, at his residence in Petchaburi. The incriminating evidence against him was a video clip of a speech he made in 2013. As the clip continued to be shared online up until June 2014, his case was thus referred to the Military Court. He was denied bail.

On 14-15 August 2014, an arrest was made against people accused of being involved in a theatrical performance, “The Wolf Bride,” which was deemed to insult the King. Two persons, Pativat and Pornthip, were arrested. The case against them had been reported at 13 police stations nationwide in 2013 by a group of zealous nationalists who produced a DVD recording of the play. However, the arrest was not made until after the coup. On 23 February 2015, the Criminal Court sentenced them to five years each, but this was reduced to two years and six months since they pled guilty.

On 15 October 2014, Opas was nabbed by a security officer at Seacon Square shopping center and brought to the military. He was accused of writing graffiti deemed insulting to the King on a bathroom wall in the shopping center. He was denied bail by the Military Court during the trial even though he suffered from diabetes retinopathy and high blood pressure.

On 13 November 2014, military and police officials raided and arrested “Kawee” at his residence in Surin at dawn. He was accused of creating two YouTube accounts, “Muang Prang” and “Noo Maew,” from which a number of video clips deemed insulting to the King had been uploaded. His detention was extended by the Criminal Court on 19 November 2014. He has not applied for bail as he cannot afford it.

On 15 November 2014, Lt. Col. Burin Thongprapai reported a Facebook page which featured posts deemed insulting to the King to the Crime Suppression Division. The following morning, Jaruwan, a factory worker from Ratchaburi, whose name appeared as the owner of the Facebook account, contacted the police to inform them that her name had been used by other people without her permission to create the Facebook account. The police officials picked her up from her home and later pressed charges against her and requested permission from the Military Court to hold her in custody. Jaruwan’s boyfriend, Anond, and Chartchai, his friend, were arrested as part of the same case. All three were denied bail since they had no money to place as deposit. Jaruwan suspected that Chartchai used her name to create the Facebook account.

On 26 November 2014, police officials arrested Bundit Aneeya, who was acquitted by the Supreme Court early in 2014, while he was speaking during a public seminar on land reform. The event was organized by the Innovation Party. Approval to extend his detention was sought from the Military Court, but on 28 November 2014, he was granted bail given his frail health by placing a 400,000 baht cash deposit.

On 11 December 2014, plainclothes police officials arrested Piya near his home. He was accused of creating a Facebook page under the name “Mr. Pongsathorn Bunthon” and the profile picture featured Piya’s photo. The Facebook page was found to feature a portrait of the King with some insulting remarks. Piya admitted that the picture was his, but said that he did not own the Facebook account. At the time of the writing of this report, he is being held in custody at the Bangkok Remand Prison.

On 18 December 2014, plainclothes police officials arrested Tiansutham, aka “Sira”. He was accused of creating a Facebook account bearing the name “Yai Dangdued” which featured posts deemed insulting to the King. After being held in custody and subject to interrogation in a military camp for six days, on 23 December 2014, charges were pressed against him and approval to detain him was obtained from the Military Court. He was denied bail by the Military Court.

In the six months between the coup and the end of 2014, at least 19 individuals were arrested on lèse majesté charges. Most of the offences were allegedly committed a long time ago. In only five cases were the alleged offences committed after the coup. The political climate in the aftermath of the seizure of power by the NCPO has definitely given rise to an accelerated effort to pursue lèse majesté cases.

Lèse majesté legal actions taken against those summoned and held in custody under martial law

After the coup, the NCPO issued orders to summon individuals claiming that it is in the service of, “the effective upkeep and maintenance of security and public order.” At least 666 individuals have been summoned to report themselves. While most of them are affiliated either with political groups or parties, a number of those summoned were not well-known figures.

On 24 May 2014, Sgt. Prasit, a former Pheu Thai MP, turned himself in after his name was included in NCPO Order No. 5/2014 requesting individuals to report themselves. He was then held in custody in a military camp under martial law and charged with a lèse majesté case at Choke Chai Police Station on 29 May 2014 and was then transferred to Bangkok Remand Prison. His request for bail was denied. On 3 December 2014, the Criminal Court sentenced him to five years in jail, which was reduced to two years and six months since he pled guilty. The sentence was not suspended since the Court claimed that the accused had committed a similar offence before and this time his offence was even more grave.

On 1 June 2014, the NCPO issued Order No. 44/2014 requesting 26 individuals to turn themselves in including Chaliaw, Siraphop, Khatawut and “Jakkrawut”. Chaliaw, Khatawut and “Jakkrawut” reported to the authorities as requested; Siraphop did not, but was later arrested. Lèse majesté charges were pressed against all four of them.

Chaliaw was accused of editing and uploading an audio clip deemed insulting to the King to 4Share.com. On 10 June 2014, he was brought to the Criminal Court to extend his detention and his request for bail was denied. On 29 August 2014, Chaliaw pled guilty to the charge against him and was sentenced to three years, which was then reduced to a suspended sentence of one year and six months. The case is pending in the Appeal Court.

Khatawut was accused of hosting an internet radio program featuring content deemed insulting to the King. On 10 June 2014, he was brought to the Criminal Court to extend his detention; on 22 August 2014, he was brought to the Military Court to seek permission to extend his detention. Given that the audio clip is still available online, it was interpreted that his offence is ongoing and thus his case falls under the jurisdiction of the Military Court. On 18 November 2014, Khatawut pled guilty to the charge against him and was sentenced by the Military Court to ten years imprisonment, which was then reduced to five years.

“Jakkrawut” reported himself to the authorities on 13 June 2014 and has been held in custody ever since. He was accused of posting nine Facebook messages deemed insulting to the King. Previously, he was held in custody by the police in 2012, but no prosecution against him followed. After the coup, on 31 July 2014, he was sentenced to 27 years and 36 months, which was then reduced to 13 years and 24 months, given that he pled guilty and previously received treatment for mental illness.

Siraphop was arrested on 25 June 2014. He was accused of adopting a pseudonym, “Rungsira,” and posting articles and poems deemed insulting to the King on Facebook. Someone reported him to the police prior to this instance. Initially, he was brought to the Criminal Court to extend his detention, and then his case was transferred to the Military Court given that the posts in question are still accessible. The case against Siraphop is the only case after the coup in which the accused has pled not guilty and the Military Court has ordered a secret trial.

Clearly, the NCPO has made pursuing lèse majesté cases a prioritiy. They have even invoked their authority to issue orders and invoked martial law to hold persons in custody for seven days without pressing any charges against them. At least five individuals who have been summoned have subsequently had Article 112 charges pressed against them.

Meanwhile, a number of individuals have failed to report themselves as requested by the NCPO. This has given rise to concern that if the individuals decide to turn themselves in or if they are arrested later, the number of lèse majesté cases will certainly skyrocket.

In sum, there has been a marked increase in lèse majesté cases since the coup including both cases previously reported to the police and new cases. The NCPO has summoned individuals to report themselves and then pressed charges against them. There are at least five persons who have been summoned and charged as such even though they have simply exercised their right to express themselves (this excludes those who have claimed a connection with the monarchy for more mischievous reasons). As 2014 drew to a close, the number of individuals held in custody for allegedly committing lèse majesté offences had increased to 24.

Updates on Article 112 cases in process prior to the coup

On 10 July 2014, the Provincial Court of Chiang Mai read the verdict issued by the Appeal Court in a case against Assawin who was accused of claiming to have a connection with the monarchy for his personal gain. The Appeal Court overturned the acquittal verdict of the Court of First Instance and sentenced him to five years in prison. On 18 July 2014, he was released on bail while the case is pending in the Supreme Court.

On 19 September 2014, the Appeal Court upheld the verdict of the Court of First Instance and the sentence of Somyot Prueksakasemsuk to ten years in prison for editing Voice of Taksin magazine and publishing articles deemed insulting to the King in two issues in 2010. The Court suddenly scheduled the reading of the verdict on 19 September, the eighth anniversary of the 19 September 2006 coup, without providing prior notice to the accused, his lawyers or relatives.

On 28 November 2014, the Appeal Court delivered a verdict in a case stemming from a feud between two brothers, one of whom accused the other of committing lèse majesté. The accused was previously acquitted by the Court of First Instance in September 2013. The Appeal Court upheld this verdict as the evidence presented by the prosecution failed to prove the guilt of the accused beyond doubt.

New and emerging challenges and trends in the fight against lèse majesté cases in 2014

Civilians are now processed in the Military Court

Normally, the Military Court only has jurisdiction over cases involving defendants who are active duty military officers. Nevertheless, the NCPO issued Announcement No. 37/2014 on 25 May 2014 to empower the Military Court to process cases against civilians who have become defendants in cases related to national security, including lèse majesté cases.

According to a strict interpretation of the law, cases that fall under the jurisdiction of the Military Court per NCPO Announcement No. 37/2014 must stem from an act committed after the announcement went into effect. But there have been at least four cases in which the alleged offences were committed prior to the issuance of Announcement No. 37, yet the accused are still being processed in the Military Court. This includes the cases against Thanut, Khathawuth, Sirapob and Somsak.

All the court cases are similar in that all offences have allegedly been committed online and according to the interpretation of the Military Court, since the incriminating content is still available and accessible on the internet, it can be assumed that the offence has been committed continually from the past until present.

Secret trials

Prior to the coup, secret trials were the exception rather than the norm. In the past five years from 2010 to 2014, the civilian courts have tried at least 41 lèse majesté cases, of which only 4 were conducted behind closed doors, and the remaining 37 were public trials. It is a fundamental right of all defendants to have observers present during the hearings in order to ensure transparency and the proper proceeding of the trial.

After the coup, the trials of Khathawuth, Somsak Pakdidech and Sirapob were conducted behind closed doors by the order of the Bangkok Military Court. In addition, the case against Thanet, which was tried in the Criminal Court, was also ordered to be conducted in secret. It is very likely that any other cases tried by the Court will be conducted behind closed doors as well.

Simply to require a civilian to be tried in a Military Court already creates doubts about the judicial process for the public, but that the accused has to face a trial in a special situation whereby they have no chance to appeal the verdict is even more worrisome. Conducting the hearings publicly with the presence of outside observers is a safeguard that helps make the accused feel a degree of confidence that the trial will be conducted fairly. But when the Court orders a trial to be conducted behind closed doors, this safeguard is undermined.

No photocopying of case material is allowed

In order to ensure the right of an accused to fully prepare his defense, he should be entitled to access all materials related to the case. In addition, his lawyer shall normally have permission to make a copy of such materials including the plaint, the testimonies, the official summary of proceedings in the court (docket) and the verdicts.

But in the trials of Khathawuth and Sirapob in the Bangkok Military Court, the defense lawyers were not allowed to make copies of the materials, including the docket. The trials were conducted in secret even though the docket of the hearing simply revealed that the Court ordered the trial to be conducted secretly and the accused asked to defer his giving of evidence and the new dates for evidence taking. None of the content in the dockets is related to anything sensitive to national security.

The Military Court has doubled the punishment

The length of punishment for lèse majesté convictions range from three to fifteen years per count. In the past five years from 2010 to 2014, civilian courts have convicted the accused in at least 31 lèse majesté cases; the length of punishment was two years/count in two cases, three years/count in seven cases, four years/count in two cases, five years/count in seventeen cases, and six years/count in three cases. On average, the punishment meted out by civilian courts was 4.4 years/count.

Thusfar, two verdicts have been made by the Military Court. In the case against Khathawuth, he was sentenced to ten years/count, prior to a reduction to five years/count given that he pled guilty. In the case against Somsak, he was sentenced to nine years/count, prior to a reduction to four years and six months/count given that he pled guilty. On average, sentences by the Military Court have amounted to 9.5 years/count.

Reconciliation hearings: a civil procedure in a criminal case?

In the case against Akkharadet, the Criminal Court proposed a reconciliation hearing, a method often used in civil procedures whereby the prosecution and the defendant meet and reconcile or broker a deal instead of going ahead with the normal hearing process and examination of the case.

Normally, a lèse majesté case is a non-compoundable criminal offence against the state and no comprise can be sought. In addition, the prosecution does not have the authority to strike a deal with the defendant. Until this point, the defendant had pled not guilty to the charge. Following this hearing, he reversed his prior decision and pled guilty. These facts coupled together could not help but raise doubts that the Court dominated the reconciliation process and assumed the role of the prosecution to negotiate directly with the accused.

Infringement on privacy and perpetuation of the climate of fear

After the coup, a new trend emerged in which upon arrest or reporting oneself to the authorities, the officials seized the personal communication devices of the arrestees or the persons summoned to report themselves, and then searched the devices in order to obtain incriminating evidence against the persons. For example, upon being apprehended during an anti-coup demonstration, Apichat’s mobile phone was seized and lèse majesté charges were later pressed against him simply due to the data found by officials on his phone.

If the seizure of devices and accessing of personal information as such has become the norm during arrests of individuals based on political motivations, it will invariably perpetuate the climate of fear as it demonstrates that the state can arbitrarily infringe on individual privacy. It will also very likely lead to a sharp increase in the number of lèse majesté cases.

The use of Article 112 of the Criminal Code to crack down on crime rings that cite their connection with the monarchy in order to commit embezzlement

Prior to 2014, there were two cases regarding the use of a connection with the monarchy to commit embezzlement, namely the cases of Prachuab and Asssawin. But, at the end of 2014, the big news that made headlines regarded a massive crackdown and arrest of at least sixteen individuals with three others remaining at large for whom arrest warrants had been issued. They were accused of working as a gang that claimed a connection with the monarchy in order to commit embezzlement, led by Pol Lt Gen Pongpat Chayapan, the former head of the Central Investigation Bureau.

In addition, it was reported that at least four other individuals have been arrested and face legal action under Article 112 for claiming to have a close connection with the monarchy. [Click here for more details: http://freedom.ilaw.or.th/en/blog/112falseclaims]

A wrap-up for 2014 and new challenges in 2015

Early in the year, it seemed that the climate was more favorable to the exercise of the right to freedom of expression vis-à-vis the use of the lèse majesté law. A number of verdicts were given in favor of defendants and society in general. But during the post-coup period, the situation has been turned upside down and it has given rise to one of the toughest times as far as the enforcement of the draconian lèse majesté law is concerned.

Apart from the skyrocketing of the number of lèse majesté cases, civilian defendants have been tried by the Military Court. In addition, the rights of defendants have been restricted in various ways, including the use of secret trials and the meting out of sentences twice as harsh as those in the civilian courts. The situation that appeared to slowly move one step forward early in 2014 had instead made three steps backward by the end of the year. In addition, the situation seems set to become even more tense in the near future.

As 2014 drew to a close, the number of those incarcerated under Article 112 of the Criminal Code had increased to a new high of 24, in comparison to the previous high of 13 after the 2010 uprising. It is very likely that the number will continue to increase in 2015. The trend of denial of requests for bail has not been stemmed and instead continues to worsen. Further, defendants tend to choose to plead guilty to the charges against them since there is only a glimmer of hope that they can fight the charges under the dictatorial military regime. The interpretation of the law has been widened to include a range of new acts, and it has exacerbated the climate of fear and caused a complete blackout of the exercise of the right to freedom of expression countrywide.

It is likely that in 2015 the lèse majesté law will be applied in new and different ways to criminalize any political acts and the accused in such cases will face ever more daunting criminal procedures.