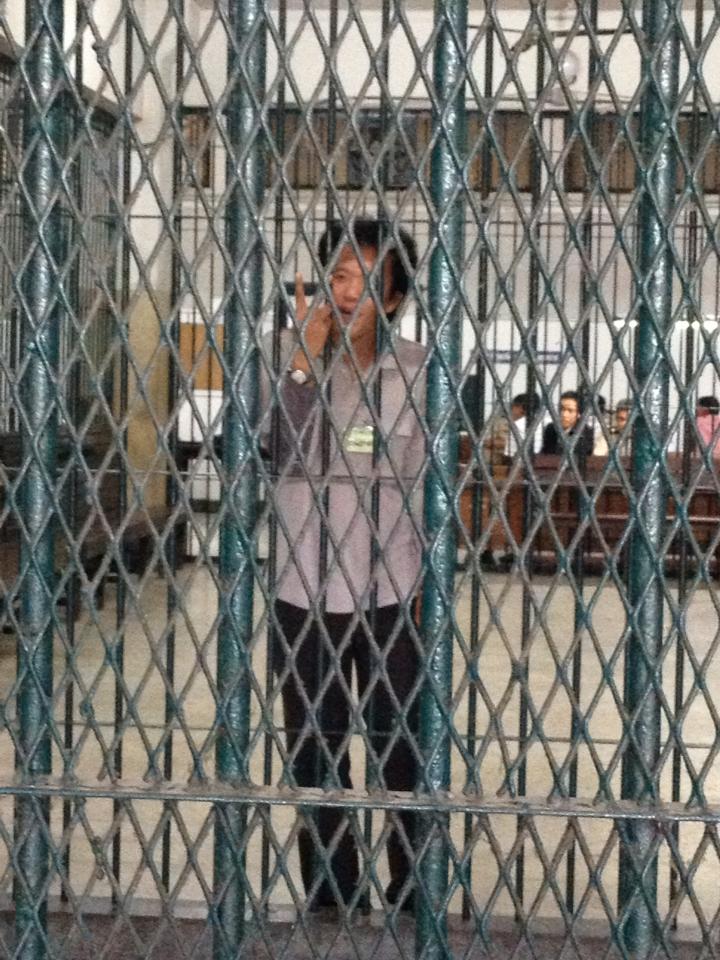

On 28 March 2013, the Criminal Court read its verdict sentencing Ekkachai H. to five years’ imprisonment and a 100,000 baht fine. Because the defendant’s testimony was useful, the court reduced the sentence by a third, to three years and four months in jail and a 66,666 baht fine. Ekkachai was found guilty, firstly under Article 112 of the Criminal Code, for defaming, insulting or threatening the Heir Apparent, and secondly under Articles 53 and 82 of the 2008 Film and Video Act, for selling videos without the permission of the registrar.

The five-year jail term for violating Article 112 and the minimum fine for operating a video-selling business without permission are in line with court verdicts in similar previous cases. But some observations can be made regarding the court’s application of the law in this particular case.

The use of royalist ideology in Thai society as a basis for the sentence

The verdict said that, in considering whether the content of the documentary of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation on CD and of the Wikileaks articles sold by the defendant violated the law, ‘it is necessary to consider the place of the monarchy in the feelings of the Thai people, as manifest in Article 2 of the 2007 Constitution, which states that Thailand has a democratic system of government with the King as head of state; Article 8, which states that the King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated; Article 70, which states that everyone shall have a duty to uphold the nation, religions, the King, and the democratic form of government with the King as head of state; and finally Article 77, which states that the state must protect the monarchy.’

This reasoning of the court has points which should be considered. According to the verdict, the defendant’s offence in this case was defaming, insulting or threatening both the Queen and the Heir Apparent since the CDs and Wikileaks documents refer to the behaviour of the Queen and the Heir Apparent. However the court instead stated the offence of the defendant must be judged by Articles 2 and 8 of the Constitution, which refer only to the position of ‘the King’ as an ‘individual’ who occupies this position, and not ‘the monarchy’, and therefore does not include the ‘Queen’ or ‘Heir Apparent’.

The citation of the court of the duty of individuals and the state to protect the institution of the monarchy under Articles 70 and 77, are similarly irrelevant to this case, because the defendant already testified that he disseminated messages in order to point out how politicians made reference to the Queen, so that the public could help each other condemn them. If the court punishes the defendant by citing the reason that individuals and the state have the duty to protect the institution of the monarchy, this is the equivalent of the court monopolizing the ways to protect the institution, which are limited to only those used by the court.

These citations are therefore the glorification of an ideology of political governance according to the viewpoint of the judges in this case, with no direct relevance to the facts of the case, and should not be a reason to give any weight sufficient to use as a basis for sentencing the defendant.

We cannot discuss whether the contents of the CDs and the Wikileaks documents constitute a criminal offence, since disclosing the contents publicly might itself constitute a violation of the law. Without sufficient information, we cannot analyse this issue, but the court, which is the party judging this case, with the authority to access all relevant information, has no reason to cite political ideology as a basis for a judgment or for considering whether the contents of the CDs and documents that the defendant was selling constitute an offence. The court must judge on the basis of the elements of the law. If it is defamation of a third party and is reason for the defamed party to suffer damage, it is likely to constitute an offence of defamation. If it is a lessening of the dignity of the accused, it is likely to constitute defamation. The court, which has both the authority and duty to judge the facts and the law in this matter, has no necessity whatever to bring up for citation provisions of the constitution that are irrelevant to the facts of the case.

The problem of using a royalist ideology to explain the reasons for its verdict, even if it is incorrect or does not directly answer the point, is that to use it as a reason to punish an individual detracts from the dignity of the monarchy. Using an ideology of belief as a reason for punishing a person who has no bargaining power at all may have a negative effect on the monarchy and may also itself constitute a violation of Article 77 of the Constitution on the duty to protect the monarchy.

The court further stated: ‘Not only in the law, but also in the feelings of the Thai people toward the monarchy which gives supreme respect, worship and admiration since ancient times, any verbal insult, insinuation or sarcasm which causes irritation to His Majesty is prohibited’. The question here is whether it is appropriate to cite the feelings of people in society at a certain period as an element in interpreting the law and a verdict. People’s feelings are tied to their experiences in each era. To use the feelings of the people is liable to change interpretations of the text of the law according to the social environment.

A criminal offence must take into consideration the ‘intent’ of the accused, not the understanding of a ‘reasonable person’

The defendant and defence witnesses testified that when viewing the CD documentary and reading the documents that the defendant was selling, they did not feel that the Queen and the Heir Apparent were injured. The defendant contended that he had no intention to defame, insult or threaten the Queen or the Heir Apparent.

The court may or may not believe the defendant’s claim but it is interesting that the court verdict said:

‘In deciding whether the defendant had the intention to defame or insult, it is necessary to look at the understanding of a reasonable person who reads the content [in the documentary and the Wikileaks documents], and not the understanding or feeling of the defendant.’

In a criminal case with implications for the right to freedom of expression, it is necessary to base the judgment on the intent in the mind of the defendant. If the defendant has no intent, there cannot be an offence. Judgment of intent, which is a matter of mind, must look at the behaviour of the act and other contingent components. If the court refers to the educational history and work of the defendant, the method of selling CDs on the day of the incident, the history of political activism, past expressions of loyalty by the defendant, etc., these are reasons to indicate intent in the mind of the defendant. These factors are believed to be contingent behaviour which may be used to analyse intent. For example, the court established that the defendant sold CDs and documents at Red Siam rallies when Surachai Sae Dam was arrested and prosecuted under Article 112. The court therefore concluded that the defendant had the intent that the recipients feel loathing in this case, no matter whether the defendant or anyone else agrees with the discretion of the court. But at least the court analysed according to the principles of case judgment.

But the court’s judgment of the intent of the defendant may not have been a consideration according to the understanding of the defendant, but examination of the understanding of a ‘reasonable person’. Such a judgment goes seriously against the principle of the criminal responsibility of the defendant.

In this case, the prosecution did not present any evidence at all on the understanding of the ‘reasonable person’, meaning that it did not present any ordinary person or any expert to testify how they felt when they saw the content of the CDs and read the messages in the documents. There was only the testimony of the police officer who decided to proceed with this case who could not be used as a representative of the reasonable person. The understanding of the ‘reasonable person’ cited in the verdict is therefore merely the understanding according to the ‘personal’ standards of the judges in this case. Given that the court has the authority to exercise its judgment, the court should have made explicit these standards by judging the existing facts applied to the relevant laws by clearly declaring in the verdict which parts of the CDs and documents damaged the Queen and the Heir Apparent, and how this was done. This is what the court should have done but did not. Instead, it heedlessly cited the understanding of the ‘reasonable person’, although there is no legal principle to support this.

Judgment of the standards of the ‘reasonable person’ is a principle that appears in issues related to assets, for example in the standard of care of assets held in trust, the standard of management of assets on behalf of a minor, the standard of caution used before signing a contract, etc. If there is a dispute between two parties whether another party has done their duty with sufficient care, one party will claim that duty has been done in the best way, but the damaged party will claim that insufficient care was taken. It is therefore necessary to use the standard of care of the ‘reasonable person’ as the standard for deciding. This standard, even though it is not clear, is the middle-level standard depending on the contingent facts of the case. But it is not used to go further to claim what the thoughts are of each person in their mind.

But the principles of criminal law are different because it is a matter of the rights and freedoms of the defendant, not a dispute over property. The fault of the defendant in a criminal case must involve considering the ‘intent’ of the defendant. For this reason, the expression ‘reasonable person’ does not appear in the Criminal Code and is not a principle of criminal law. If the defendant claims no intent, and the prosecution has not proved beyond reasonable doubt, or the court has not seen other circumstantial behaviour that can indicate the intent of the defendant, then to cite a principle of the Civil and Commercial Code that, according to the understanding of a ‘reasonable person’ in general, the defendant is likely to be guilty is to declare the defendant guilty by giving an incorrect reason.

The selling of the CDs which may be offensive without permission is a single act and is a single offence

In this case, the court gave the brief analysis that “… the acts by the accused constitute many separate offences calling for punishment for each offence, according to Article 91 of the Criminal Code.”

The court gave no reason why the sale of CDs constituted many acts when the act which was the sale of CDs at one time, on one day, and for one disk, with one intent by the defendant. But the court instead judged that this constituted multiple offences and each offence must be punished on both charges.

In this case the court may have judged according to the precedent of Supreme Court ruling 3218/2549 and other similar rulings. Case 3218/2549 involves the abduction of a minor to commit indecent acts. The court judged that the abduction of the minor and the indecent acts were offences against different persons since the offence of abduction of the minor was an offence against the guardianship of the parents, whereas the offence of committing indecent acts was an offence against the minor herself. The law aims to protect different injured parties. The acts of the defendant therefore had two separate intents. They were multiple offences, and must be punished as separate offences.

However, Supreme Court Case 3218/2549 punished the defendant for multiple separate offences not merely because the relevant laws have the objective of protecting different injured parties, but also because there were ‘acts’ which occurred on separate occasions. The offence of abduction of a minor was complete when the abduction took place and the offence of indecent acts was complete when the indecent acts took place, which may be in a different context and at a different time. It is enough to be able to separate the two when the relevant laws protect different injured parties, in order to see multiple offences or multiple acts.

The facts in the above verdict of the Supreme Court Case are different those in Ekkachai’s case. The crime of defaming the Queen and the Crown Prince is completed when the defamatory message has reached the third party. The crime of unauthorised selling of videos is completed only when the selling is completed. (The mere act of downloading videos into CDs would not constitute such crime.) In Ekkachai’s case, both the crime of defamation and the crime of unauthorised selling of videos were completed at the same time, that is, when he sold the CDs to a third party. Given the difference between Ekkachai’s case and the 3218/2549 case, the conclusion of the 3128/2549 case, that the accused committed two separate instances of crime, cannot apply.

Although the two charges in the complaint in this case aim at different protections, i.e the offence of selling CDs without authorization aims to protect regulation of the industry and offences under Article 112 aim to protect the honour of the Queen and Heir Apparent, when the defendant was prosecuted in this case for his act, i.e. the sale as a physical act on a single occasion, this cannot be seen as an incident that can be counted as ‘multiple’ different offences as in the verdict in this case. If the correct verdict is guilty, the act of the defendant is a single offence but a violation of multiple laws. According to Article 90 of the Criminal Code, the court must impose only the most severe penalty, which is according to Article 112, and cannot also impose a penalty for the unauthorised selling of videos.

The accused sold CDS of ‘films’, not ‘videos’, and did not operate a business

The court’s ruling in the verdict that the defendant was guilty of operating a business in selling videos or CDs without permission under Article 54 of the 2008 Film and Video Act is a clear misapplication of the law.

Point 1. According to the understanding of the general public, CDs may be called ‘videos’, but the 2008 Film and Video Act gives the following definitions.

‘Film’ means material that has a recording of images, or images with sounds, which can be shown as continuously moving images, but which is not a video.

‘Video’ means material that has a recording of images, or images with sounds, which can be shown as continuously moving images in the form of a game, a karaoke with pictures, or in any other form as specified by ministerial regulation.’

The CDs in this prosecution contained a documentary of moving pictures with both images and sounds, of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, about Thai politics and Article 112 of the Thai Criminal Code, which can be shown as continuously moving images. But the viewer can only view and cannot interact. They do not have the form of a game or karaoke or anything of a similar form. Hence in this case the defendant sold CDs containing a ‘film’ and not a ‘video’.

The court order to punish the defendant under Article 54 considered in conjunction with Article 82 of the 2008 Film and Video Act, for engaging in the business of renting, exchanging or selling videos commercially or by receiving benefits in compensation, without permission, is therefore a misapplication of the law, because it is a provision concerning only videos. If the interpretation of law requires punishment for selling films without permission under Article 38, which concerns engaging in the business of renting, exchanging or selling films commercially or by receiving benefits in compensation, without permission, then a different penalty applies.

Point 2. The act of the defendant was to sell only two CDs for 20 baht each. The method of sale did not involve setting up any shop. It involved merely packing the CDs in his bag and selling them as he walked. The defendant contested the case by saying that he intended to disseminate information, rather than to seek profit from sales and at political protests there were normally many CDs on sale, without anyone having to seek permission. The act of the defendant may therefore not be held to constitute ‘engaging in a business’ as provided in the law. The defendant therefore should not have been found guilty under either Article 38 or Article 54 of the 2008 Film and Video Act.

The 2008 Film and Video Act is one law that has been widely criticised in society following a case in the news in which a rubbish collector collected old CDs and sold them without permission and was found guilty under Article 38 considered in conjunction with Article 79. In this case the defendant was sentenced to a fine of 200,000 baht, reduced to 100,000 baht because the accused confessed. The case produced shock and showed the public that this law should be amended. While the law has not been amended, the court should not apply the law too strictly, and should interpret it in a way that would benefit the rights and freedoms of the accused.

This case has attracted media attention from both within Thailand and abroad, partly because it involves Article 112, an Australian news agency and information from a well-known website like Wikileaks, and because it is a criminal case where the verdict directly restricts the rights of the defendant. It is therefore necessary to show the problems of legal interpretation and the restrictions to the rights of the people that may ensue if this verdict is used as a precedent for verdicts in future cases.

Translated by Prach Panchakunathorn

English editor: Alec Bamform

Read the summary of the verdict here (translated by Pipob Udomittipong)

Reference: คดีนายเอกชัย คนขายซีดีสารคดีเอบีซีและเอกสารวิกิลีกส์ (Ekkachai: seller of ABC’s news documentary CD and Wikileaks cables)

RELATED POSTS

No related posts