Throughout the period under the rule of the NCPO, the enforcement and prosecution toward individuals by “ lèse majesté law ” according to Article 112 of the Criminal Code, is one of the most interesting public issue. Even if this phenomenon has continuously happened since year 2007, there is a sharp increase of enforcing this law after the 2014 coup with hided certain meanings. Meanwhile, the military has played a vital role in terms of prosecuting, summoning, apprehending, investigating, searching, accusing of offenders, and until reaching the highest position of the judicial process by authorizing judicial power to the military court which resulted in the severe punishment, delayed trails, and denial of right to bail.

After the death of the King Rama XI since 2016, the situation has reached the highest tension when certain people expressed their opinions in the negative way that caused general people felt uncomfortable. Therefore, the Article 112 of the Criminal Code is widely interpreted in order to prosecute any forms of expression, and there was a phenomenon of the lynch law when people physically attacked or gathered to pressure other people, who expressed negative opinion, directly at their residences or toward their families.

On the other hand, the situation of prosecution, under Article 112 of the Criminal Code, which has been intense since the NCPO staged the coup, has begun to reduce the tension between the midyear 2017 until year 2018. There was a phenomenon of non-prosecution orders as well as dismissal verdicts for the defendants who confessed. Overall, entering to the year 2018, the huge change was a practice that the Attorney General need to inquire all Lèse majesté in order to be more careful. According to data collected from October 2017 until 22 May 2018, there is no new accusation luanched under Article 112 from opinion expression.

Article 112 under “The Green Justice Industry”

The political situation had been strained since the 2006 coup and last until the redshirt crackdown in 2009 and 2010. It had sparked people to come out and widely express their political views which sometimes might have content in the manner that made general people think of the Monarchy, both online and other public spaces. The political stages, for example. Many people who saw this kind of expression report to police. Also, there still are some overdue cases that left with the inquiry officers as well as public prosecutors.

After the coup on 22 May 2014, one of the initial efforts that the NCPO attempted to do is to bring those cases back to the cour. Furthermore, bringing the Lèse majesté defendants into the justice process and normal court trial seemed not fast enough for the NCPO. Thus, the martial law was exercised by authorizing military officer to play a role for prosecuting these cases.

Initially, exercising prerogative power of the military could be seen from the NCPO orders that summoned people who used to join a political movements and forced them to approach the secret investigation in military camps. There were at least 400 people summoned by using the NCPO orders. At least 3 orders were attempts to charge suspects or find more information relevant to the offence under the Article 112. For instance, the NCPO order no. 5/2014 summoned certain scholars of the Nitirat group, who had made a movement to amend the Article 112, as well as the activists, who had made a movement with the red shirts and the former Lèse majesté prisoners who had recently been released.

Then, NCPO order no.6/2014 was issued and summoned Pravit Rojanaphruk, a journalist who usually expressed his opinion against Article 112 on the social media. After that NCPO order no. 44/2014 was issued to summon total 28 persons, and at least 3 persons in this list were summoned and charged under Article 112 by military immediately.

Military Court, the last procedure of military justice over civillians under NCPO

For summoning and detaining people for 7 days, the NCPO primarily practiced by power of martial law. Later on, it was transformed to be the NCPO order no. 3/2015 by issued virtue of the Section 44 of the Interim Constitution. Therefore, this kind of authority still remained with military throughout the period of the NCPO but just gradually changed the name and the enforcement mehod in order to keep non-violent image of the military.

Besides, issuing orders that summoned people and forced into judicial process, military also cooperated with police and exercised their power to arrest the Lèse majesté defendants such as the case of “Tanet,” the case of Thanat, also known as Tom dundee, the case of Sirapoth, the case of Chayapa, and many other cases. Actually, police could exercise their normal legal power and perform their duty for these cases, but military unseemly stepped in. Meanwhile, in the case of Bundhit although he was arrested by police, there were armed military officers, detecting his rented room as well.

.jpg)

At the same time, for some certain suspects, even though they were arrested by police in accordance with normal procedure, they were later sent to the military camp for interrogation and “attitude adjustment” like suspects who were arrested by military special power. For instance, in the case of Tanakorn or Burin, soldiers took them from the police station while they were there. From iLaw’s observation, for these cases under the NCPO period, actually many of the cases had happened before the NCPO coup. For instance, in the case of Tanat or Tom Dandee who made a speech since 2010, and in the case of Banphot network, the political analysis programs were uploaded on the internet since 2010 continuously.

Military not only involve in the Lèse majesté cases as police, but they also performed duty as the court. Owing to the NCPO announcement no. 37/2014, it prescribed that even though a defendant was a civilian, the order allowed the militay court to have jurisdiction to try the case. This announcement had affected on people who committed the crime since 25th May 2014 until 12th September 2017 (the first day of the Head of NCPO order no. 55/2016 to end a military court jurisdiction over new cases). These people who committed the crime during this period were investigated by the military court.

As iLaw had collected information, from at least 94 accused who were charged under 112 under Lèse majesté offense during the NCPO period, 57 people were prosecuted before military courts. Six people were not prosecuted ; 20 people still were in the trial process ; 29 persons has been sentenced already. Moreover, there were only two persons who were grant punishment suspension. Another two persons had no current information, and there is no information which cases the military court has dismissed.

For the Lèse majesté cases under military court, if a defendant confessed, the court could provide the sentence within one day, so the case would end quickly. On the other hand, if the defendant insisted to fight the case, the proceeding of the case would consume much longer time. For example, for the case of Siriphob, the court arranged an appointment to have witness examination since the 13th november 2017 until now only two witnesses just have testified. Furthermore, in the case of Tara, it had taken at least two years, and the witness examination was postponed at least three times. As a result, the defendant decided to give up as he wanted the case to end quicker.

The punishment for Lèse majesté cases in the military court was another interesting topic as the military court usually give sentence per act more severe than the civillian court. Therefore, the case of Wichai was sentenced with the highest punishment for 70 years for posting total 10 messages (1 message per 7 years), or for the case of Pongsak, the military court sentenced 60-year imprisonment due to 6 Facebook statuses (a status per 10 year).

During the regime of military dominance, from the collected data, there were the new accusations under Article 112 in year 2014 against at least 24 people and in year 2015 against at least 37 people.

The refugees still not repatriated, but there is a marked development in Cambodia.

The NCPO summoned people who had participated in movements about the Article 112 as well as many people who had been accused of the Article 112. It created the intimidating atmosphere during 2014. A lot of people felt insecure about their own safety ; thereby, there was a phenomenon of political refugees. Each refugee had different reasons for fleeing abroad. Some of them escaped because they concern on their own security and freedom, and some of them fled as they refused to comply with the NCPO summon.

There is no information or statistic that confirmed number and status of those political refugees. However, there were some of well-known public figures. Particularly, Somsak Jeamteerasakul, a former professor at Thammasat University, was in the name list in the order no. 5/2014, so he decided not to report and deleted his Facebook account. He reappeared on his Facebook on 22 November 2014. Another example is Pavin Chachavalpongpun previously instructed in a foreign country, but he occasionally came back to Thailand for conducting a television program. Moreover, Jaran Ditthapichai, a former professor at Rangsit university and the former committee of the first National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (NHRC), had fled already and acquired French citizenship on June 2017.

.jpg)

Furthermore, many political activists such as Ekaphob aka “Tang Achiwa”, Saran aka “Aum Neko,” Chanoknan aka “Cartoon,” Watt Wanyangul, a writer, and Jom petchpradab, are the people who publicly announced that they would move to other countries in order to ask for the refugee status owing to political reason.

The NCPO also made a movement intermittently about the refugee issue. For example, on October 2016, there was a report from local media of Cambodia that Thai government asked for cooperation with Cambodian government to send the Lèse majesté offenders back and prosecute them in Thailand. One month later, General Paiboon Kumshaya, the Justice Minister gave an interview that the Thai government still did not give up to keep track of these people to bring them to enter the judicial process, but it has to practice according to the international laws. In the beginning of year 2017, the foreign commission of the National Legislative Assembly (NLA) attempted to cooperate with the foreign commission of Laos for extraditing the Lèse majesté suspects to get the punishment in Thailand.

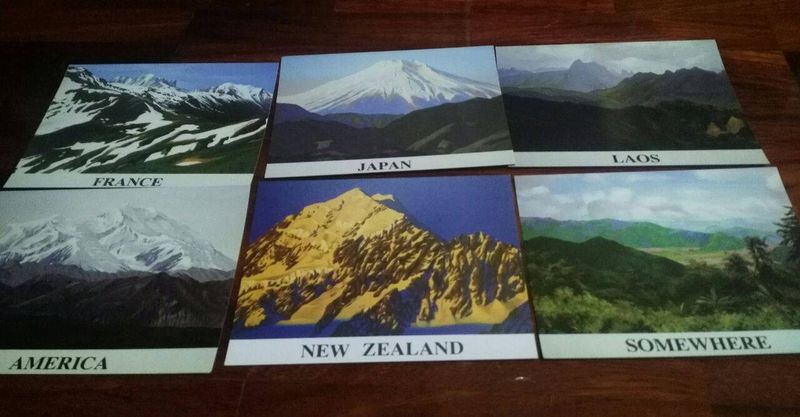

Postcard Setไกลบ้าน, an art with attempt to communicate on refugees by displaying mountains in countries where Thai refugees live

Recently, on April 2018, the Laos Ministry of National Defence reported that there would have cooperation with Thai officials to keep track of the refugees who might express in the manner of defamation toward the monarchy or cause damages to Thailand. Even though, there is still no report about the extradition according to the Article 112 of the Criminal Code, but it still has some information that Ittipon aka “Dj Sunho” disappeared while he was in Laos. Also, Wutipong aka “ Kohti” was arrested by some people, who looked like in soldiers uniform, and then disappeared from the shelter in Cambodia.

For many years, there is no extradition from neighbor countries because the neighbor countries did not employ the same law as “the Lèse-majesté law,” as Thailand. It is therefore undoable according to International Law, but on 14 February 2018 , Cambodian Parliament passed the bill to amend the Criminal Code. By imposing the punishment and the fine toward individuals who might have the manner in the way that defames the monarchy in Cambodia, this legal change might affect on the refugee extradition from Cambodia to Thailand will become easier in the future as the action is the guilty as well under the Cambodian law.

A refugee gave an opinion to Prachatai that the purpose of this law is likely to be enforce with political opponents against the Cambodian government, not for the refugees, but it left such a concern that in the future the refugees could be repatriated as well.

The outrage phenomenon and the case of “Pai Daodin” : The huge storm before the situation became relieved

On 13 October 2016, The Television Pool of Thailand stopped broadcasting normal programmes. Instead, it broadcasted a statement from the Royal Household Bureau with the black and white graphic. Afterward, there was the official announcement that His Majesty, Rama IX, had passed away. Since then, the atmosphere in Thailand had fallen into the grief and sadness. Also, there was an announcement that the government officers, the employees in the state-owned company, and public officers had been in mourn for a year, and for ordinary people, they could mourn properly.

Among the mournful atmospheres, during the first 2-3 weeks, another phenomenon happened at the same time as well when certain groups of social media users expressed in the way that caused people feel discomfortable or made them feel that it was improper for the situation in specific time. Some people viewed that these kinds of comments were against the Article 112. The situation was getting more severe when many people felt dissatisfied in various areas. Not only did they complain to the law enforcement officers, but they also used the social sanctions.

.jpg)

For instance, during the nighttime on 14 October 2016, thousands of people gathered together in front of the soy milk store in Phuket Province after someone found that the owner’s son posted a message which was likely to be in the scope of the defamation toward the king. Furthermore, a banner showing dissatisfaction and anger was hung in the front of the store. Gathering had continued almost three hours from 11.30 p.m until 02.30 a.m, and then it ended when the former leader of PDRC negotiated with the crowd that he would be a representative to file legal complaint against that person.

Later, on 15 October nighttime, a group of people gathered at a roti & tea store in Phang Nga Province after someone had seen and insisted that a naval officer, the owner’s son, posted message within in the scope of defamation toward the king. The blockage tensely carried on until a deputy governor came to negotiate with the crowd, and he would investigate and bring a result within 15 days, so the crowd started to disperse.

The most severe incident is the case in Pan Thong District in Chonburi Province, on 18 october 2016, there was a broadcasted video about “K” A young man wearing a purple shirt was brought by a group of people to the police station in order to prosecute him. “K” was beaten by a group of people who took him out of his apartment. Then “K” was prosecuted before the Chonburi Provincial Court, but he denied all charges. At present, this case still be on the trial in the court.

People in Phuket gathered in front of soy milk store and hung signs, souece:Prachatai

For the Lèse-majesté cases that happened after the death of the King and gain biggest publicly recognized is the case of Jatupat or “Pai Daodin”, a student activist who was accused of sharing an article about biography of the King Rama X from the BBCThai website and set as a public. Before Jatupat was prosecuted under Articel 112, he had participated many activities against the military coup. He was prosecuted at least 4 charges, and he was well-known among political followers. Even though the society has paid attention to this case, the request for bail was refused at least 8 times. Meanwhile, the witness examination that occured in August was full of tension because of having both a secret trial and observation from the military. Eventually, the Khon Kaen provincial court has sentenced Jatupat for 2 years and 6 months.

Jatupat or “Pai Daodin”, a well-known Lèse-majesté prisoner for sharing BBCThai article

During the mournful situation, there were may reports about dissatisfaction from people, and there were many arrested offenders. Nevertheless, iLaw cannot confirmed all information. As iLaw can verify, there were the new accusations under Article 112 in 2016 at least 15 persons and in 2017 at least 18 persons.

The year 2019, there is no new case and relieved situation?

As iLaw has been documenting informantion, we have found that, since the beginning of the year 2018 until the 22th May 2018, there is no new accusation under Article 112, and some certain cases were prone to relieve. For instance, the case of Sulak Silvaluk, he was accused of discussing about the Thai history during the King Naresuan period, which probably was within the scope of defamation toward the king. The military prosecutor of the Bangkok military court issued a non-prosecution order. For the case of Tanat aka “Tom Dundee”, on his fourth case that he was accused of giving a speech within scope of defamation toward the King in Lamphun province. In this case, Tanat pleaded guilty in the Criminal Court, and the court dismissed the case because the fact according to the plaintiff’s complaint was not fall under the element of Article 112.

For other interesting movements which illustrated the less exercising of the Article 112, for instance, the five defendants, who were arrested in accordance with the Head of NCPO order no. 3/2015 and accused of sharing Somsak Jeamteerasakul’ Facebook status, were released from the ฺBangkok Remand Prison after having been kept in remand for 84 days. On 4 January 2019, the Narathiwat Provincial court has sentenced Nurahayati, a blind muslim girl who was accused of posting Gilles Ungpakorn’s article on her Facebook, so she has been sentenced for 6 month (which was reduced to three years owing to her confession), but on 23 January 2018, the court has allowed to bail her out in the appeal court.

Suluck, a Lèse-majesté accused went to report at Bangkok Military Court

Meanwhile, a significant change was that the Office of the Attorney General has released a regulation which specified that the attorney general will examine Lèse-majesté cases and give an order himself to have more caution. The public prosecutors who responsible for any cases must immediately send the files to the Office of Attorney General without any opinions and this practice must be hold in both the Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court. Therefore, it is marked that whether the alteration of the prosecutorial discretion would affect on the filtration of the cases during the prosecution process which become more strict in terms of legal interpretation.

RELATED POSTS

No related posts