ByJayshendra Karunakaren

The military coup against the elected Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government in 1973 occurred due to the government’s radical political reform efforts in reforming the legislature and in nationalising major industries. The military tribunals prosecuted its political opponents using the 1958 Law of State Security and the 1972 Arms Control Law, that was ironically, enacted by the Allende government.

Pictuer from keepitsurreal

Background – 1973 military and judiciary coup against elected radical dictatorship

In the years preceding the military coup against Salvador Allende’s elected government in 1973, Chile experienced a period of successfully consolidated democracy. However, the executive branch accorded itself greater powers and the military assumed a greater political role.

The Popular Unity government of President Allende, who was elected by a small majority of votes, faced opposition from the judiciary and the military due to the former’s support of labour rights. In addition, the government wanted to replace the unicameral Congress with a bicameral legislature and to accord itself the power to appoint Supreme Court justices. Moreover, the government nationalised banks, coal mines, and major private companies. Furthermore, the government, supported by activists from the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionario (Movement of the Revolutionary Left) attempted to create popular courts (outside of the traditional court structures) in major cities to manage the problem of land invasions.

During Allende’s regime, workers gained more rights and protections, and thus increased land invasions, strikes and factory takeovers. The Supreme Court responded to the increase in labour organization by lobbying for the Allende government to execute policy decisions within constitutional limits set by the traditional courts.

In September 1973, the Supreme Court declared that Chile faced a ‘breakdown of the legal order’ due to the ‘illegal acts of the administrative authorities’, and subsequently led the protest against the government. This political polarization resulted in the rise of armed groups on the political right and the left, and ensuing violence. In response, Congress amended the 1958 Law of State Security to transfer cases of confiscation of unauthorised arms and the prosecution of the owners of these weapons from the jurisdiction of civilian courts to military courts. The new amendment not only prohibited individuals from possessing firearms without permission from military authorities but also the formation of militias. These factors led to General Augusto Pinochet and the Chilean army to launch a coup against the Allende government in 1973, with the aid and support of the US.

The original justification of the military coup was due to the alleged violations of the rule of law by the Popular Unity government. The Supreme Court supported and collaborated closely with the Pinochet regime as observed by the declaration by Supreme Court president Enrique Urrutia Manzano congratulating the armed forces after the coup. Importantly, despite the Supreme Court possessing the power of judicial review, it never exercised its duty during the military dictatorship.

Possession of weapons tried at wartime military courts

In the first few days of the coup, the military replaced civil and penal law and suspended Congress and the constitution. In addition, the military declared a state of emergency, imposed a curfew, summoned individuals to the Ministry of Defense, outlawed public assembly and conducted extrajudicial executions. The new power amended the Arms Control law and the Law of State Security to increasing penalties to the death penalty.

However, in prosecuting its opponents, the military regime used the 1958 Law of State Security and the Arms Control Law which was ironically, passed under the elected Allende government in 1972. Significantly, the junta transferred cases of violations of these two laws from “peacetime” military courts to “wartime” military courts. The junta’s use of laws in military courts stems from the legal framework prior to the coup, and from the expansion of executive prerogatives after the coup.

Picture of Gen. Pinochet from maximoberrios

No right to appeal, no cross-examinations, 200 sentenced to death

During the first five years of the regime, military commanders were put in charge of territorial units throughout the country and created “wartime” military tribunals (Consejos de Guerra) through an executive decree issued on September 22, 1973. These tribunals consisted of seven military officers directly under their command and, for the most part, did not have prior legal training.

In these procedures, the defendants had few effective rights, no right of appeal and faced rapid verdicts and punitive sentencing, including the death penalty. However, at the end of 1978, political prisoners were tried in ‘peacetime’ military courts where trials were slower and thus, greater procedural rights were protected. Nonetheless, military courts of the first instance were still isolated from the civilian judiciary and was located on military bases.

Defendants and their lawyers were not permitted to conduct cross-examinations of the prosecution’s witnesses. Relevant evidence could also be kept secret by military prosecutors. In addition, there was no minimum time allowed for the defense to prepare its case.

Chilean military court laws were applied retroactively. While the law creating wartime military tribunals was issued on September 22, 1973, there were cases of defendants being charged in wartime courts for crimes committed before September 22.

While there was a civilian Supreme Court that should traditionally be placed on a higher rank than military tribunals, the Supreme Court stood aside military courts dispensed summary judgements. Trials by the tribunals were rapid (conducted within a few days). The courts tried and estimated 6,000 people in the first five years of military rule, with approximately 200 sentenced to death.

According to the database and research complied by the Vicaria de la Solidaridad (Vicariate of Solidarity, an organization established by the Catholic Church and Protestant churches), 43 percent of cases involved infractions of the 1972 Arms Control Law, 55 percent concerned violations of the 1958 Law of State Security, and 2 percent were for violations of the code of military justice or traditional criminal law). These laws were present prior to the coup, and was used by the Allende government.

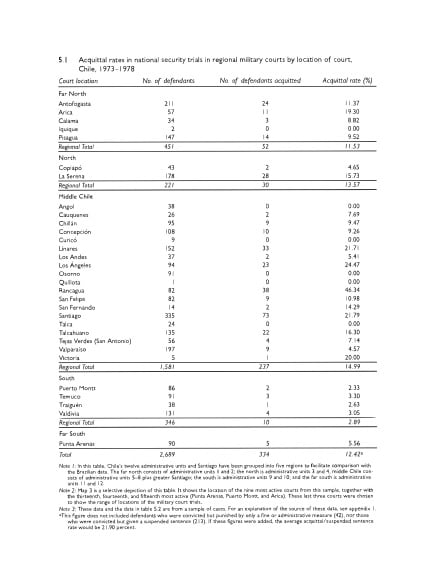

The data used by Perreira is based on a large sample (over 2,000 defendants) of Chilean military court cases from 1973 to 1978. The average acquittal rate is at 12.42 percent. 6 local military courts dealing with a total of 165 political prisoners did not acquit a single defendant.

Severe disproportionate punishment for crimes of thought

The four cases demonstrated below shows the punitive and disproportionate to the crime committed sentencing handed down by regional military courts in Chile for the crimes of peaceful expression of dissent:

– A defendant was described as “an individual with the ideas of the left, a militant of the Socialist Party, a Marxist who provoked disorder in public acts and political meetings…. shouting slogans aimed at provoking violence and frightening people.” While this was clearly a case of crimes of though and expression, however the defendant was sentenced to 3 years in prison for violating articles of the Law of State Security.

– A taxi driver, who was sentenced to 540 days (almost a year and a half) for insulting policemen while drunk (violating article 417 of the military justice code). His sentencing justification states that the defendant was a “socialist militant.”

– Another person receiving the same sentence for the same charge (as above) for the crime of stating to policemen that “the military who killed the president were assassins.”

– 9 defendants were convicted of crimes committed before the coup and sentenced to prison of 400 to 1000 days. They were accused of being members of the Socialist Party of Algarrobo, forming a Che Guavara group that propagated “doctrines that tend to destroy the constituted social order,” and forming paramilitary groups with “the object of practicing self-defense and attack.” The defendants were found guilty of violating both the Arms Control and State Security laws.

– Six armed men were caught by policemen 5 days after the coup were suspected of planning an assault on a police station. They were convicted of violating article 8 of the Arms Control Law. Two of them were sentenced to death the day after they were apprehended and were executed by firing squad, while 4 others received prison sentences of 3 to 4 years each. The only evidence that the men had planned to attack the police station were confessions most likely extracted through torture.

Analysing the variation of acquittal rates between different regions is important to indicate the consistency of military justice. In Chile, military courts in different regions did not acquit defendants at similar rates, the south and far south regions were more punitive towards defendants with acquittal rates of only 2.89 and 5.56 percent respectively. This is vastly different to the 14.16 percent average for other regions. The acquittal rate in middle Chile was five times as high as in the south. The most heavily populated regions in Chile had the highest acquittal rates while courts in peripheral areas had lower acquittal rates. This is demonstrated in The table below:

Transparency of trials and social movement:

Criticisms of legal decisions are generally not aired in the press. The Vicaria de la Solidaridad was the legal movement established by the Catholic church and Protestant churches and consisted of human rights lawyers to represent defendants in military courts. It was the only organization that provided defense lawyers for political prisoners. However, their efforts in protecting defendants were limited as the Supreme Court only accepted 30 of almost 9,000 habeas corpus petitions filed during the Pinochet regime. However, their legal actions successfully established a record of the defendants.

In 1979, Judge Servando Jordan required Manuel Contreras and two other members of the intelligence agency DINA to testify in court in a case involving the discovery of several bodies in the Manip River delta. However, the case was closed due to insufficient evidence.

In 1983, appeals court judge Carlos Cerda investigated the disappearance of 12 communist party members in 1976 and charged 38 members of the carabineros and airforce for the murder. However, the Supreme Court closed the case after several appeals, ruling that the defendants were protected by the 1978 amnesty law. The Supreme Court then censured Judge Cerda when he persisted with the investigation.

These dismissal of cases reveal that the Chile’s highly centralised and hierarchical judiciary (which is controlled by the conservative Supreme Court) proved to be a pillar for authoritarian rule during the Pinochet regime. The regime sanctioned judges who investigated human rights

……………………………………..

(N.B.: The information, data sets and tables are obtained from Anthony W. Pereira’s book Political (in) justice: authoritarianism and the rule of law in Brazil, Chile, and Argentina).

RELATED POSTS

No related posts