(อ่านบทสรุปย่อภาษาไทยได้ที่นี่)

The Impacts of the Computer-related Crimes Act B.E. 2550 (CCA) and State Policies on the Right to Freedom of Expression aims to explore implications of the enforcement of CCA since it came into force in July 2007 until December 2011 vis-à-vis state policies as well as public reaction toward the law and its enforcement in comparison to the situation abroad.

Findings on the enforcement of the CCA

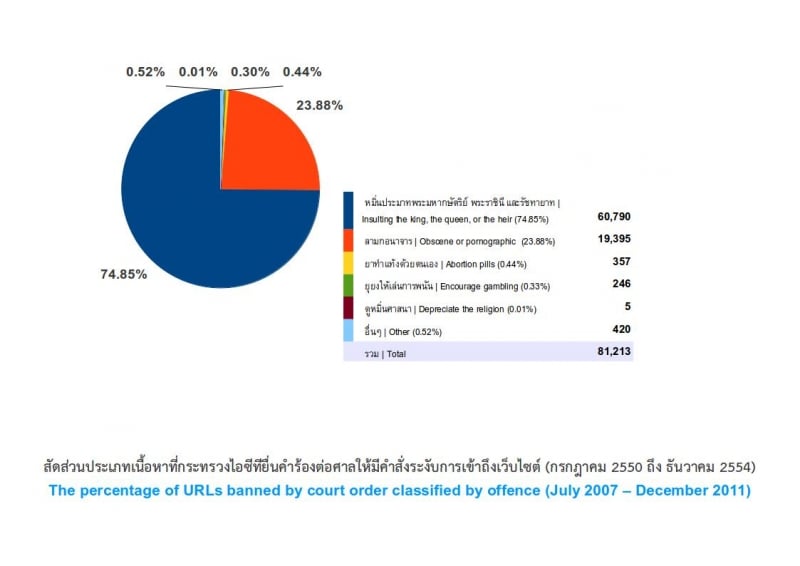

It was found that during the entire period of four years and six months when the CCA has been in force, 156 orders have been issued by the Courts invoking Section 20 of the CCA to ban access to content or the entire website of a total of 81,213 URLs. The most frequently blocked content concerns information and images deemed to insult and defame the King, Queen, Heir-apparent, or Regent, for which 90 court orders have been issued to block access to 60,790 URLs, or approximately 75% of the total. This is followed by the blocking of access to pornographic content and images with 52 court orders blocking 19,395 URLs, or 24% of the total. The remain 1% concern content involving abortion medication or self-abortion methods, gambling or blasphemy, bogus and Pharming websites, and websites which might cause misunderstanding about the containment and suppression of demonstrations and which could lead to public commotion or stir up people’s resistance.

2009 saw the highest number of court orders issued to block website requested by the Ministry of Information Communication and Technology (MICT); 64 orders suppressed access to 28,705 URLs. 2010 saw the biggest number of websites blocked, 45,357 URLs, by 45 court orders. Though checks and balance mechanisms are built into the law requiring the Courts to review and use their discretion prior to issuing orders, in reality, because problems of urgency, the number of URLs involved and the other responsibilities of the Courts, it was found that the judiciary could not have spent much time reviewing the requests. For example, in 2009 and 2010, an enormous number of URLs were the subject of requests to the Court. On average, the Court issued orders to block access to 326 URLs per day in 2009 and 986 in 2010. The data shows that of 156 orders, 142 were issued on the same day the requests were submitted by MICT.

One dominant factor contributing to the blocking of access to websites in Thailand is the intense political conflicts that have led to a surge of the use of social media to express political views. Nevertheless, Section 20 of the CCA to block access is enforced in normal situations; during emergencies, the Thai state has other legal provisions to which they can resort to restrict expression of views, i.e., a declaration of emergency and enforcement of the Emergency Decree, or informal requests for cooperation from Internet Service Providers to block certain websites, etc.

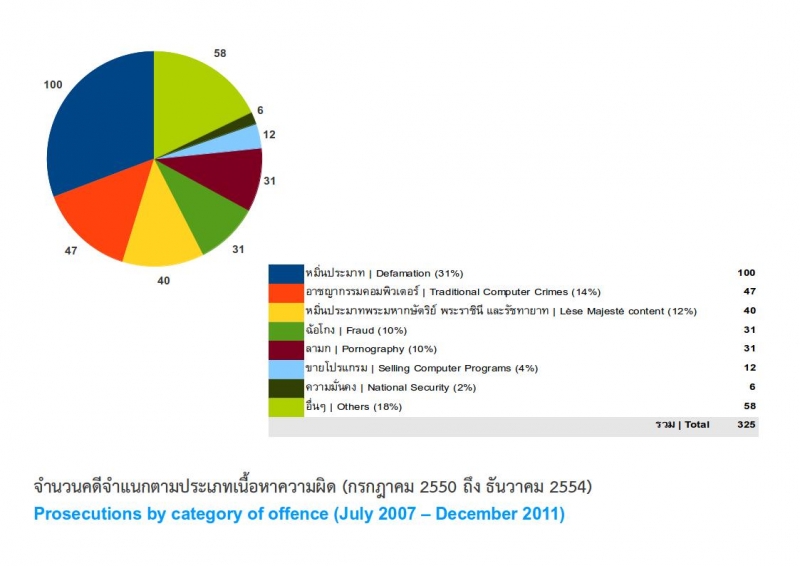

It was found that throughout the period the CCA was in force, 325 legal cases were filed. Though one of the basic aims of enacting the CCA was to fill a legal loophole and crack down on conventional computer-related crime, it was found that 66.15% of prosecutions related to the dissemination of allegedly offensive information under Sections 14-16, and only 19% of the cases directly involved offences concerning infringement of computer systems or data (conventional computer-related crime). Prosecutions involved: (1) libel (100 cases), (2) conventional computer related crime (47), (3) lèse majesté (40), (4) electronic fraud or cheating (31), (5) dissemination of pornographic material (31), (6) illegal distribution of software (12), (7) information regarding national security (six); 58 cases were unclassified. Most of those accused and prosecuted were men (153 cases), followed by women (67) and intermediaries or ISPs (26), with the remainder unclassified.

Based on interviews and group discussions eliciting opinions regarding enforcement of the CCA with informants from state agencies, ISPs and webmasters, it was found that one unique feature of the law is it provides clearer definitions and procedures for blocking websites, requests and submission of computer traffic information. However, despite these procedures, informal requests for “cooperation” from the authorities claimed urgency still persist.

One problem shared by various informants is a lack of confidence in the interpretation by law by state officials and law enforcement officials of Section 14 (1) or the definition of the phrase “intentionally supporting or consenting to” in Section 15 with respect to intermediaries. A lack of knowledge and understanding regarding elements of the crime and enforcement of the law was also found among personnel in the judicial process. One state official opined that a special court should be established to try the cases with help from associate judges who are knowledgeable in computer science and technology.

Webmasters or website administrators tended to the view that the CCA seems to impose disproportionate liability on intermediaries or service providers, forcing them to filter content posted by users. Some websites had to overhaul their structure by requiring prior registration of users for posting messages. Thus, the law tends to infringe, rather than protect freedom. ISPs wanted the levels of liability to be clearly spelled out in law and clear procedures on how to proceed with any information or content deemed illegal (takedown procedures). The state should adopt a policy to encourage ISPs to monitor themselves, instead of imposing penalties on intermediaries. As the law exists to prevent the commission of offences, they also thought it is important to develop mechanisms to protect the personal information of internet users. It was agreed among ISPs that blocking websites is still a necessary measure, but not one that should be used by the state too often. The state should also acknowledge that website blocking is not an effective or direct solution. More effort should be put into solving problems at their root causes, by identifying and prosecuting the real perpetrators. Most webmasters thought a multilateral committee should be established to review blocking requests, in place of the Courts.

Analysis of problems regarding provisions in the CCA

The analysis of legal provisions and state policies found the CCA has a direct impact on the right to freedom of information and opinion online. Problems found during the study include:

Definition issues. For example, the term “service provider” in paragraph 3 of Section 4 fails to clearly define and classify types of “service provider”, showing a lack of understanding of reality and the technology. It requires all kinds of service providers to keep computer traffic logs and be indiscriminately held responsible for the dissemination of content uploaded by others. Certain service providers who are not involved with illegal information have consequently been held liable.

Criminality issues concerning provisions in Sections 14, 15 and 20 of the CCA. One fundamental aim of the CCA is to address conventional computer-related crime which cannot be dealt with under the Criminal Code there are different elements of the crimes. But it was found the CCA has been used mainly to suppress internet content and thus has direct implications for the rights and freedoms of the people.

Section 14 (1) was intended to address bogus or fraudulent computer data, to close a loophole regarding document counterfeiting. It was found that in reality this Section has been used mainly for libel prosecutions, even though libel offences are already actionable under either the Civil or Criminal Code. When a charge of libel is brought to the Court under the CCA, the offence becomes non-compoundable, preventing any mediation between the conflicting parties. It also allows any persons to make accusations. Other problems in interpretation make it difficult to decide if the accused should be allowed to prove the truth of a statement in order to be exempt from prosecution or penalty. The current interpretation of Section 14 (1) may cause confusion and simply ensures that libel charges under the CCA carry more severe penalties than this under the Criminal Code.

Section 14 (2) is also often used in conjunction with charges concerning national security. In terms of the extent of enforcement, Section 14 (2) is one of the most controversial legal provisions. Its use by the state has been criticized as infringing on the people’s right to freedom of expression. It contains vague and ambiguous phrases such as “damage to security” and “causing public panic”, which are in breach of the “legality principle” or criminal law safeguards concerning the “certainty of law”. The Section fails to establish clearly for ordinary people what kind of information is an offence against the law. State officials are allowed broad discretion in interpreting the law, creating a danger that the law becomes subject to excessive or arbitrary interpretation and eventually a tool of political suppression.

Section 14 (3) also deals with offences regarding the dissemination of security information. However, the elements of crime are spelled out more clearly than in Section 14 (2) since it is linked to offences in the Criminal Code. The question has thus arisen as to why both Section 14 (2) and Section 14 (3) are part of the same law.

Many prosecutions under Section 14 (2) and (3) are made in conjunction with the use of Section 112 of the Criminal Code regarding lèse majesté. A comprehensive examination of the provisions and enforcement of the CCA and infringement of the people’s freedoms in the virtual world cannot avoid discussion of the content, enforcement and ideology underlying interpretation of Section 112 of the Criminal Code. Essentially, Section 112 can be considered as subject to individual discretion. The law allows anyone to report a case. As a result, the law has been used as a tool against others. And because it carries heavy and disproportionate penalties, including imprisonment of three to fifteen years, and provides no grounds for exemption from either liability and penalty, it allows no opportunity for the accused to prove the truth of what is said.

Another problem stemming from the CCA is legal redundancy. Section 14 (1) on the dissemination of false information causing damage to another party has in practice been used for legal actions for defamation. Section 14 (3) also overlaps with Section 14 (2).regarding national security offences and Section 14 (4) regarding dissemination of pornographic materials is similar to Section 287 of the Criminal Code. In practice, it was found that this Section has been used merely to request court orders to block websites, rather than for prosecutions.

Section 15 provides for liability of service providers. Apart from the lack of a clear definition of the term “service provider” already mentioned, this Section sets a rate of penalties for service providers as the same as that for perpetrators. This is unreasonable and disproportionate. In many instances, service providers simply act as an “intermediary” transmitting online data. According to the Criminal Code, service providers should be held responsible only as “supporters” rather than “principals”. As a result, a number of service providers have decided to “self-censor”, leading to an infringement on the people’s right to freedom of expression. Apart from problems with the CCA, Thailand has no internet content monitoring procedures by which service providers can decide to take down certain information from their servers without having to wait for a court order (Notice and Takedown). The state has no clear procedure to identify the persons mandated to advise service providers on which data could be actionable. There are no clear notification procedures, no details of the information required to be submitted to the state to establish the existence of an offence and no clear guidelines on a grace period for service providers to delete data after being notified. As a result, enforcement of the law has failed to follow any standard pattern, and has been subject mainly to the discretion of individual officials relying on informal cooperation.

Section 20 deals with suppression of information dissemination and website closure, considered urgent measures by the state to prevent commission of an offence. But the Section contains vague definitions of offensive content. Restriction on access to information should be based on clear definitions with clear conditions and procedures, based on the principle for upholding freedom of information and expression. Blocking websites should be used as a last resort, only when necessary under “exceptional” circumstances because of the extensive impact on the rights of the people. This Section allows the state to operate without having to go through any prior judicial oversight. The findings of the study on website blocking and prosecutions show that in reality, Section 20 has been used as a “primary” tool.

Comparative study of online control laws and state policies in other countries

Germany, Malaysia, the USA and China all pledge to uphold the rights to freedom of expression and information as prescribed in their constitutions. Exceptions or restrictions on freedoms do exist and vary from country to country. For example, Germany does not protect any content harmful to children and youth and to peace, content that offends human dignity, racism and dissemination of German nationalism (Nazism). USA has only one restriction imposed on content deemed harmful to children and youth. China restricts content regarding national security and government stability. Malaysia does not protect content affecting national security, blasphemy, pornography and obscenity, and content harmful to children and youth. However, none of these countries have computer-related laws on the dissemination of such information. In addition, they have no law that imposes the same tariff of penalties on both the service providers as intermediaries and the principals who disseminate the information. Both China and Malaysia try to monitor internet content by making it a “duty” of ISPs.

Websites are blocked in all countries, though frequency (as far as it has been reported and identified) and the way this authority is used seem to differ. In Germany, quite a few website are blocked through orders derived from clearly defined laws and under the principle of proportionality. Despite this, orders usually meet strong opposition. The state is often taken to Court to fight closure orders. In the US, a few websites have been blocked informally based on the exercise of state power through ISPs and there is a special agency to monitor and issue blocking orders. China and Thailand seem to rely heavily on blocking websites and tend to have vaguely defined legal provisions. Those affected by state orders are often not informed in advance and many cases happen informally. Websites are rarely blocked in Malaysia, since such orders are not feasible due to other protective laws; the state often uses other ways to control content such as by clamping down on civil rights, or prosecuting online news networks on security-related charges. It should be noted that the underlying perspectives that prompt the Thai authorities to clamp down on websites are quite unique. While other countries, including China, normally use measures discreetly and avoid media publicity, every government in Thailand has proudly presented in press conferences the number of websites blocked.

With regard to intimidation of people or netizens, China and Malaysia frequently arrest netizens under a number of national security laws in force. In Thailand, arrests and attempts to threaten netizens have not been regular, mostly coinciding with political conflict. The study shows the numbers rose significantly during street protests against the government, particularly after the 19 September 2006 coup. In addition, while in other countries, service providers are often spared (since they merely provided a service, but were not involved with disseminating content), in Thailand, the authorities force ISPs to take responsibility for acts committed by others.

In terms of movements and reactions of the people toward the law and state policies, people in Germany and the US have more channels through which they can express themselves than in the East. People there can demonstrate, launch opposition campaigns, organize seminars to educate society, write open letters and appeal cases to higher courts, while movements in China, Malaysia and Thailand are often restricted to calls for social justice and policy. There are few demands for effective law enforcement as in the West.

Recommendations

Legal recommendations. The CCA should be a criminal law specifying offences and penalties for conventional computer related crime or any criminal action directly against the system or data, i.e., unauthorized access, data interference, data theft, etc., in order to fill out the legal loophole and to address legal redundancies. Should the state insist on applying it with any illegal data disseminated online, then the provisions have to be made clearly and unambiguous and it should serve the purpose of existing offences in other relevant laws. In fact, it could be easier if the state simply amend the exist Criminal Code and add new computer related criminal offences in there.

The definition of “service provider” should be spelled out to correctly describe the functionalities and duties and should just refer to service providers of computer system or network only. It should not be expanded to also cover other telecommunication operators who are quit irrelevant to the content and not involved with the computer related crime.

In terms of liability and penalty rate of the service providers concerned with the dissemination of illegal content, the law drafters should classify levels of liability and types of ISPs in light of the content. For example, the ISPs might be held liable for the content, but technical service providers should not be held liable for any content at all. An exception can happen, for example, if it could be proven that the technicians are also involved with recruiting, revising or modifying the data. If the law drafters insist on holding the service providers liable for the offence committed by their users or by their clients, then the law should not impose the same penalties on both the service providers and the perpetrators. But they should be imposed proportionately and fit the principle of multiple culprits.

As for measures to suppress content or to block websites, Section 20 should be amended to make it clear and not prone to be subjected to individual discretions. It should rest on the principle that if the suppression does not take place soon enough, massive damage could have happened. Or if the impact of such dissemination of information is irreversible, the law should provide for clear and written methods, process and conditions for the exercise of suppression power. And the ISPs should be informed of such procedures. After the website is blocked, other process should commence including prosecution against the person who has disseminate the data that has led to the blockade of website. If in the end, it was found that the content is not illegal, the order has to be rescinded by the court and remedies should be provided for the damage parties. In addition, there should be a body of knowledgeable persons who are representatives from various parties and are able to develop the review process as well as to oppose the order.

Policy recommendation The state should develop measures to monitor online content while striking the balance with the protection of people’s freedom. Instead of website blockade, other measures such as the promotion of self-monitoring among users and ISPs should be encouraged. In addition, an effort should be made to increase knowledge in computer technology among state officials. The state should endeavor to establish a special court to try computer related offences and to develop handbooks, guidelines, or commentaries of concerned laws and regulations. In addition, a code of conduct should be developed by the operators. The policy and measures should be geared toward creating incentives among the operators, instead of stressing the suppression or punishment such as tax incentives.

Recommendation for people and ISPs Individuals and NGOs working on the issue should place an importance on the right to information and freedom of expression, stay alert and constantly monitor any attempt by the state to issue a law or regulation or policy which might infringe on the right to information and freedom of expression. This should ensure that the state does not exercise its power beyond the limits and unfairly. In addition, the ISPs might get together or form as a network of entrepreneurs to monitor and prevent the government from imposing disproportionate penalty rates on ISPs which also affect people’s rights and freedom. Most importantly, a method should be developed to oppose the unfair law and policy, to contain any arbitrary use of power, or to demand more rights and freedom. From advocating policy options, one can transcend them and keep developing clear advocacies by using law as our leverage including litigation.